When I finally finished the first big chapter in my upcoming book—about the sense of taste—I thought to myself: “Well, that was a lot more difficult than I thought it would be.” Looking forward to the next one, like an idiot I thought, “Well, how complicated can mouthfeel be?”

Like so many of these biological systems, the answer turns out to be very, very complicated. The term “mouthfeel” really does a disservice to this sensing system, as it doesn’t just happen in the mouth. It’s actually a special application of several overlapping systems we use to sense pressure, texture, heat and cold all over our bodies. It also serves as a warning system responding to high concentrations of chemicals that might be harmful. The term sensory experts use is trigeminal, after the nerves in the face through which its signals are routed.

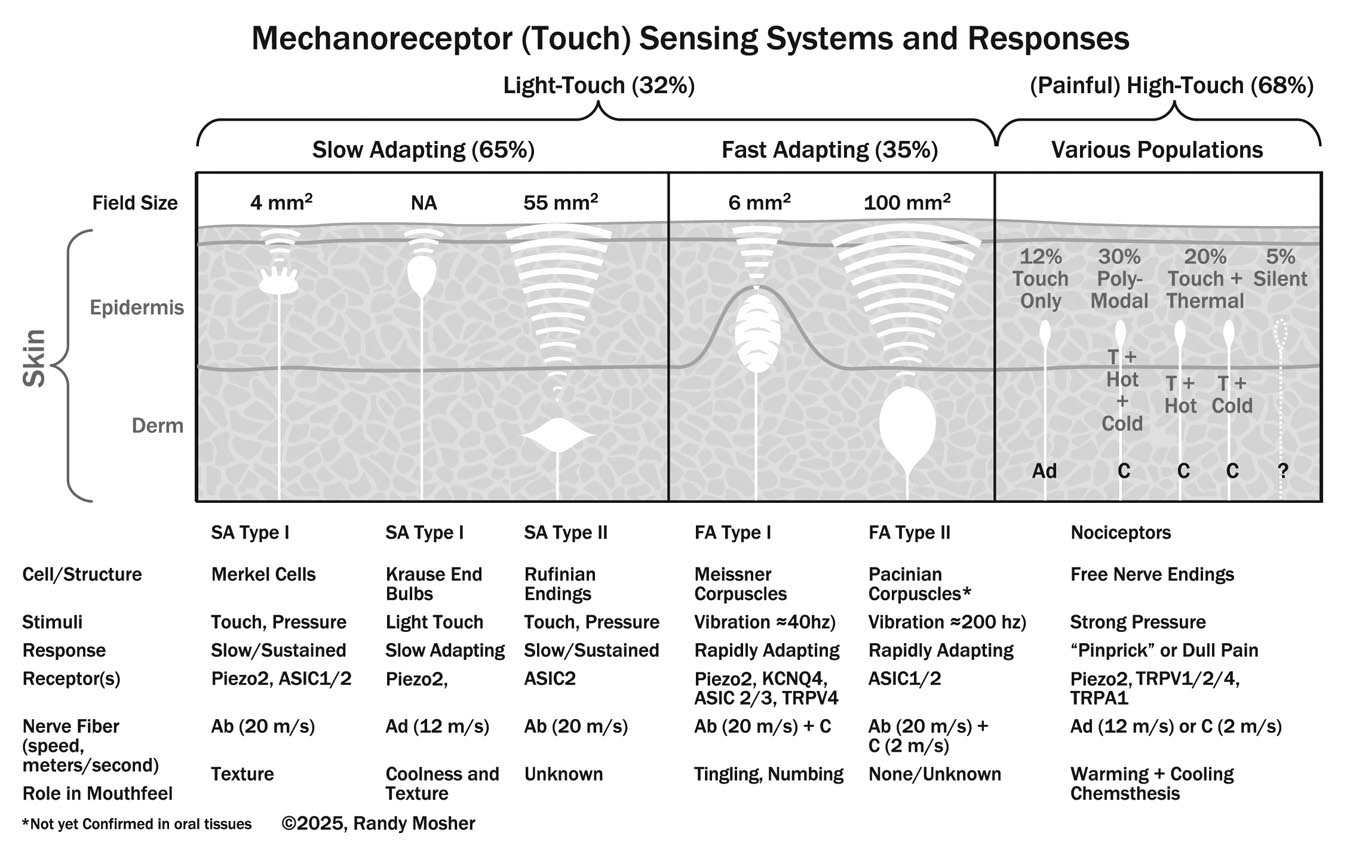

Our trigeminal system consists of multiple coordinated sensory inputs based on more than a dozen receptor types. As I often do to get a grip on a subject, I found it helpful to diagram various parts of it. As the book was getting longer and longer, we decided we could do without the diagram, so I’m presenting it here. It’s a representation of the major touch sensing systems we use for mouthfeel/trigeminal sensations.

Sensory neurons simply embedded in the skin are called “free nerve endings.” Other types are housed in specialized structures that help them perform particular tasks. Of those in housings, you’ll notice that the neurons are described as fast adapting or slow adapting. All respond to pressure, but slow adapting neurones generally respond continuously, stopping only when the pressure is removed. Although this is a critical function, these cells can’t sense vibration or texture. For that you need neurons that respond only when there is a change in pressure; once they have sent an impulse responding to that, they reset to zero. This happens very quickly, so they get every pulse of a vibration, and every little bump as we run our fingers—or tongue— across a textured surface or substance. Merkel cells and Krause end bulbs are the ones doing the fine sensing on our tongues and fingertips.

Different touch-sensitive neurons respond to differing amounts of pressure. Generally those located close to the skin surface are the most sensitive. The “high-touch” bare nerves require a good deal of pressure, but this is appropriate since they can signal with pain. As the chart shows, these nerves sort into different populations, with many also responding to chemicals by producing the same sensations stimulated by real heat or cold, as well as physical irritation. Called “chemesthesis,” this is why we feel the heat of chiles and the chill of menthol simply by their chemistry.

The mechanisms for transforming stimuli into sensations here are completely different from the G coupled-receptors used in smell and certain tastes. Instead, specialized ion channels are employed. In one case, a three-part protein expands like a camera iris to open a path for ions to enter the cell in response to torqueing of the cell wall. The admitted ions trigger electrical depolarization of the cell, leading to signaling.

Besides just being fascinating, the lesson here is that mouthfeel, which we usually lump together as kind of a catch-all, it really a constellation of different sensations. As usual in tasting, our perception benefits from thoughtful attention and the pulling apart of differing sensations for a more complete and informative picture of whatever we’re focusing on.

References and further reading:

Giulia Corniani and Hannes P. Saal, “Tactile Innervation Densities across the Whole Body,” Journal of Neurophysiology 124, no. 4 (2020): 1229–40, https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00313.2020.

Jie Zheng, “Molecular Mechanism of TRP Channels,” Comprehensive Physiology 3, no. 1, (2012): 221–42, https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c120001.

Stephen D. Roper, “TRPs in Taste and Chemesthesis,” Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology 223, (2014): 827–71, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-05161-1_5.

Patrick Haggard and Lieke De Boer, “Oral Somatosensory Awareness,” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 47 (October 4, 2014): 469–84, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.09.015.

Benjamin U. Hoffman, “Merkel Cells Activate Sensory Neural Pathways through Adrenergic Synapses,” Neuron 100, No. 6 (2018: 1401-1413, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2018.10.034.

Y. García‐Mesa, “Merkel cells and Meissner’s corpuscles in human digital skin display Piezo2 immunoreactivity,” Journal of Anatomy 231, No. 6 (2017: 978-989, https://doi.org/10.1111/joa.12688

Meghan A. Piccinin, “Histology, Meissner Corpuscle,” StatPearls, January 15 (2020), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK518980/#:~:text=Meissner%20corpuscles%20play%20an%20essential,degeneration%20of%20dermatological%20tactile%20sensation.

Amanda Zimmerman, “The gentle touch receptors of mammalian skin,” Science 346, No. 6212 (2014), https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1254229.

Yann Roudaut, “Touch Sense,” Channels 6, no. 4 (2012): 234–45, https://doi.org/10.4161/chan.22213.

Lynne U. Sneddon, “Comparative Physiology of Nociception and Pain,” Physiology 33, no. 1 (2017): 63–73, https://doi.org/10.1152/physiol.00022.2017.

Yuan-Ren Cheng, “Acid-sensing ion channels: dual function proteins for chemo-sensing and mechano-sensing,” Journal of Biomedical Science 25, No. 46 (2018),https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-018-0448-y

E.O. Anderson, “Piezo2 in Cutaneous and Proprioceptive Mechanotransduction in Vertebrates,” Current Topics in Membranes 79, January (2017): 197–217, https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.ctm.2016.11.002.

Yuanyuan Y. Wang, “TRPA1 Is a Component of the Nociceptive Response to CO2, Journal of Neuroscience, 30 No. 39 (2010): 12958-12963, https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.2715-10.2010

Yue Ji, “Chemical Composition, Sensory Properties and Application of Sichuan Pepper (Zanthoxylum Genus),” Food Science and Human Wellness 8, no. 2 (2019): 115–25, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fshw.2019.03.008