G. (probably George) Lacambre was an important brewmaster in Belgium in the first half of the nineteenth century. He wrote what he described as the “first book on Belgian beer written by a Belgian brewer.” Published in Brussels in 1851 as Traité Complet de la Fabrication des Bières, this massive two-volume set with an accompanying work on distilling was so influential that even later books like that of Catruyvels and Stammer (1888), quoted heavily from it. He seems to have been a figure that modernized Belgium’s brewing industry considerably, since the book notes a lot of new technology as well as modernized procedures for brewing beers, reducing the complexity and time needed to manageable levels. I can’t prove the connection, but this procedure has a lot of similarities to the “American” adjunct mash procedure refined an popularized by Anton Schwartz in the second half of the nineteenth century. The timing does line up, so it’s interesting to speculate that perhaps a Belgian brewer was partially responsible for the development of American Adjunct lager.

Obviously a work this large has a lot in it, so here I’m dealing with a small portion of the book where he describes the beer styles of the day. Early on in the book Lacambre asserts that at that time, just about all (75 percent) beers from Belgium and Holland were wheat (or other adjunct) based beers, even “the ones we call barley beers.” This was prior to the arrival of lagers in Belgium. Most of the beers he describes came in two forms: one with very low alcohol content and a “speciale” version somewhat stronger. “Double” was also used to refer to this stronger version, but it has nothing to do with the Trappist style dubbel we know today.

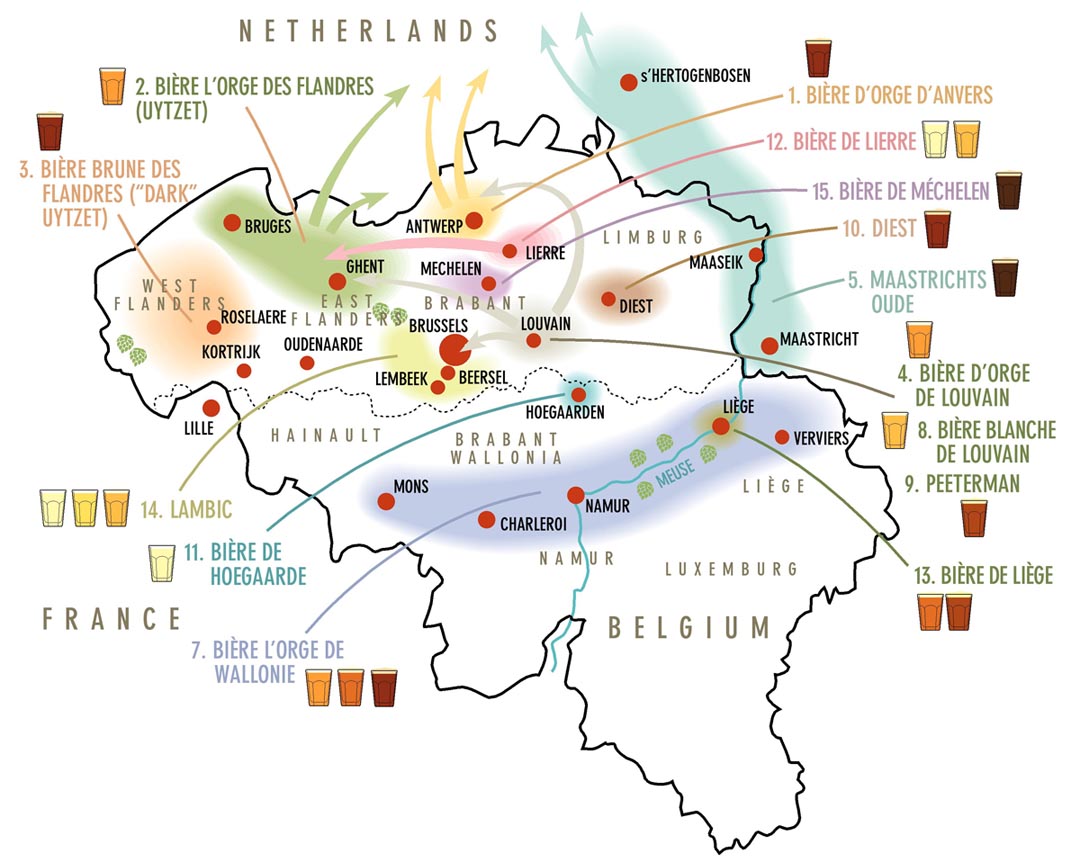

Because Belgium’s beer landscape at that time was so complex and only partially overlaps with styles we recognize today, I created this map to help me wrap my head around it all. Shaded areas indicate where certain styles were brewed; the arrows show where the beer was most exported to. The glass icons reflect what Lacambre says about the colors of the beers. Green icons indicate where they were grown in Belgium.

It’s important to note what’s missing: Trappist/abbey styles like dubbels and tripels—or any strong beers at all. Nothing we would recognize as saison, either, although the name pops up simply as a designation of a full-strength beer.

1. Bière d’Orge d’Anvers (Barley Beer of Antwerp) Mostly barley malt, with a dab of wheat (4-6%) or oats (5-8%) added, although the best ones were 100% barley, aged at least six months. As with several of these beers, chalk was sometimes added to the kettle to darken the wort by raising the pH (pretzels use a similar technique). The hops “of best quality” rate was 1 to 1.25 kg/hl. The wort for the strong version was 1.043-1.058; the weaker second runnings came in at about 1.025.

I have no direct evidence connecting the two, but this beer could conceivably have morphed into Belgian Pale ale. However, it’s also clear that a good deal of English pale ale was being imported into Belgium by 1900.

2. Bière d’Orge des Flandres (Barley Beer of Flanders) Also called Uytzet, this was brewed around Ghent. Mostly brewed from barley malt of a winter type called “sucrillon” kilned to a light “ambrée.” Also included “un peu” of wheat and/or oats. Ordinary/“simple” had alcohol of 3.2 percent. The double (export) was brewed only in winter, at 1.053–1.058, with an alcohol about 4.5 % vol.

3. Bière Brune des Flanders “Not bad,” he says. Barley malt was “torrified” in kilns, plus a little wheat and a tiny amount of oats sometimes. Similar brewing to Uytzet, with a slijm/turbid mash, but in this case the turbid portion was not added to the main mash, but was added to last runnings for a second-quality beer. Because of slow conversion of the dark malt, this beer required a long mash. Gravity was 1.040-1.055 OG. A 15–20 hour boil contributed a lot of flavor. Chalk was sometimes added, but was frowned upon by better brewers. “No two brewers do it the same way.” 500–750 grams of hops per hL were used. Aged 2–3 months. Guesstimated 22-27 IBU at 2.5%AA.

4. Bière d’Orge de Louvain Description of a barley beer brewed at Lacambre’s own aptly named “Grande Brasserie, a vast enterprise in Ghent capable of 150 hL batches using unique horizontal pressure boilers heated by steam. They brewed three beers from a malt dried in proprietary indirect kilns and described as “very lightly amber.” A weak bière de mars (single beer) at OG 1.025 (6.6°P) was made by combining all mashes; a double, from the first two mashes only, was at 1.058 OG (14°P).

The double used 5–6 kg.hL of Belgian hops, plus 16 /hLg of American hops “with plenty of perfume and very strong bitterness,” It was capable of aging 16-18 months (down to 1.022) in a “Brussels-style” fermentation. Single used just 120 grams of hops per hL. Both versions were boiled in pressure kettles at ~113°C (235 °F) for 4-6 hours, “until the right degree of color was reached.”

5. Bières de Maestricht, Masaek, Bois-le-Duc, Rotterdam. Considered by Lacambre to be “barley beers,” these bières brune were brewed along the tributaries of the Meuse river in Dutch-speaking parts of Belgium, and were popular in the interior of Holland. The malts were always darker than those used in Liège beers, which were in other ways similar. “Fort” versions brewed in winter were apparently much esteemed in Holland. Grain bill included “a certain proportion” of blé (hard wheat/durum), malted spelt, soft wheat (froment), which Lacambre states was “unimportant.” The barley malt was well modified.

A 1.5 to 2 hour infusion mash was used; conversion was slow due to the high kilning. The first two mashings were combined for the first beer, and the second two for an inferior second beer. For first (strong) beer, 625 grams of “bonne” hops per hL, with a 10 to 12 hr boil. Second beer was “much less” hoppy.

6. Bière d’Orge Wallones (Verviers, Namur, Charleroy) Similar brewing technique as bière d’Orge d’Anvers, these beers differed widely in taste, color and strength. Generally, Wallonian malt was undermodified. Small quantities of other grains, usually spelt and oats, were also used. Different boil lengths affected color: In Verviers, the beer was “amber, not brown” took 6 to 7 hrs, but in Namur and Charleroy it was”very brown,” requiring a 12 to 15 hr boil. Adding chalk was frowned upon, but was sometimes used anyway. 1 lb/hl “Meuse”(local) hops. Gravity was 1.043–1.051. Fermentation was in “petite” casks of 1.5-2 hl. Aged 4–6 months before drinking.

7. Bière d’Orge Wallones (Liège, Mons) Similar to above, but with a small percentage of hard wheat, spelt, oats, and sometimes buckwheat or even broad beans. Gravities were around 1.040. Fermentation temps were as high as 28-30 °C, but the best brewers kept them near 25 °C (77 °F).

8. Bière de Louvain Classic white beer. Proportions of the grain bill varied: barley malt 45–55%; unmalted wheat, 44–56%; oats, 6–12%. “Best versions” used 60 percent unmalted wheat, 27 percent malt and 12 percent oats oats. Some brewers cut corners by using only 1/3 of wheat, but this doesn’t produce the same taste, he says. Gravity was 1.041 (10°P), although a “kleyn” (small) version was also made: OG of 1.018 to 1.025 and alcohol at 2.25–2.5 percent.

Hopping is light at 143–167 g/hL, although he specifies “two or three year-old” hops from the regions of Alost or Poperinghe, meaning bitterness would be minimal. The final boil was 60 to 90 minutes. Lacambre says the beer was ready to drink eight to ten days after brewing, or between twelve and twenty-one days if bottled. Much longer and it would become “strongly acidic.”

Lacambre devotes fourteen pages to this style, describing a nightmarish traditional brewing procedure that involved turbid mashing and boiling the wheat wort separately from the rest. When we attempted to reproduce this for a presentation at the National Homebrewers Conference, the brewing team threw up their hands in despair after eight hours, having succeeded only in creating a “tub of wheat jelly.”

He goes on to describe a much more recognizably modern brewing procedure he had worked out. This used 61 percent air-dried barley malt plus 37 percent unmalted soft wheat, finishing at 6.25 °B, using 175 grams of Alost hops per hL.

I can find no mention in his description to the use of orange, coriander or any other culinary seasonings so associated with this style today, although he mentions them early in the book, calling them “English” spices.

9. Peetermann I have read elsewhere that this partner beer to witbier was actually the more popular of the two in the nineteenth century. The recipe was similar to bière de Louvain, above, except that the second runoff of wheat is boiled for 4–5 hours before being returned to the mash—and then it gets really complicated. There were many steps and an awful lot of boiling, often with chalk added to darken the wort and either calves feet or “stockfish” added to the kettle, which was supposed to clarify the wort, although Lacambre notes this was ineffective. The result was “very viscous and very brown in color, with a penetrating and agreeable aroma.” 1057–1074 (14–18°P) and poorly attenuated, ending at 1025–1029 (6–7.5°P); 260–500g hops/hl. Steam kettles were preferred, as the old direct-fired kettles gave the beer a “burnt” taste.

10. Bières de Diest Several styles were brewed in Diest, but most important were two strengths of the same beer, the stronger “gulde bier” or “bière de cabaret,” at 1.048–1.050 (12–12.4°P), and a weaker “bière bourgeois,” which was often simply called Diest, at 1.036/9°P. The former used 44% malt, 40% unmalted wheat and 16% oats, while the weaker version used 56% malt, 29% unmalted wheat and 15% oats. Double used 500 g/hl of hops, with “a little less” in the weaker.

Lacambre describes Diest generally as “unctuous and sweet,” and it seems to have a connotation of healthfulness as a kind of low alcohol malt-extract kind of beer, “good for mothers and infants,” according to one label I’ve seen.

Lacambre says nothing about the particular malts here, so we’re on our own. It is clear from everything that diest was a very dark beer, and It’s hard to imagine that any boil, no matter how vigorous, could transform pale malt into something “almost black” in just 5 or 6 hours. Perhaps a mix of brown and six-row to get both color and enzymes?

11. Bière de Hoegaerde A pale witbier which he describes as “of little importance” being drunk only in the immediate environs of Hoegaarde, but “very agreeable in the summertime,” with “a certain acidity and refreshing moussy quality. Brewed from 63% malt, 21% unmalted wheat and 16% oats. DeClerck, 1957, describes it as having “a very acid palate.”

12. Bières de Lierre, “Cavesse” (Liers) Brewed from 67% malt, 13 % wheat and 20% oats, at two strengths, a “forte” and an ordinary. Lacambre describes this as a “Bière jaune” (yellow beer) that had a lot in common with beers from Hoegaarde and Leuven.

13. Bières de Liége This is a bizarre pair from Eastern Belgium, although similar beers were brewed in Mons, further west. There were two strengths: a “bière jeune” (young beer) and a “bière de saison” (beer of the season, meaning it had been brewed in the proper winter brewing season, from a mix of barley and spelt malts (or sometimes just spelt malt), plus oats and wheat. With a gravity of 1.043–1.051 (10–13°P) and thick, “viscous” character, Lacambre didn’t think too much of this: “there are more bad beers than good in the summer.”

14. Bière Brune de Malines (Mechelen) A pair of dark beers, the stronger of which Lacambre describes as a “renowned” beer and important for exports. Both were prepared in a similar manner to each other and to diest. Normal grain bill is one part oats, two parts wheat and four parts well-germinated barley malt (for 22 tonnes of 225 liters = 4950 liters, 2100 livres grain are used, or 42 livres/hL. Multiple mashes were used. The first two were combined for strong beer; all four were mixed together for ordinary ale.

This beer was “very dark” due to a 10–12 hour boil, usually with chalk added. 500 grams fresh hops per hl. Usually aged 8–10 months, with 6 to 8 percent of fresh beer blended in. Longer aged beer (18 months) was blended into fresh beer at between 25 and 33 percent for “a certain taste of old beer.” This seems very much along the lines of the Flanders sour red and brown beers, although Mechelen is no longer home to that type of beer.

16. Lambic While Lacambre has a good deal to say about Lambic, much of it aligns with what has survived to this day. Eventually I’ll wade through his text on this and offer a summary.