© 2024, Randy Mosher / Craft Beer & Brewing Magazine

Beer is a chemical product driven by human imagination, created via the chemistry of plant growth, post-harvest processing, brewing and fermentation. At every step, a large part of the transformations involved in getting beer to your lips involves manipulating temperatures to achieve specific outcomes. The field of chemistry that deals with chemical reaction rates is called kinetics. The main principle of kinetics is that the higher the temperature, the faster chemical reactions occur. In a chemical reaction, the participants go from one stable state to another, overcoming a “wall” between the two by adding energy, quite often in the form of heat.

It’s obvious that weather and climate affect crops in complex ways. Once harvested, heat may be applied to a crop to reduce moisture. In malt it’s taken further, becoming an active contributor to the creation of differently-flavored malts, resulting in hundreds of flavor-active molecules that form beer’s unique malty backbone.

In the process of brewing, the objective is to manage a system of plant enzymes to break apart starches into sugars. Temperatures are one of the main levers of control. This control is what creates the difference between a highly fermentable, dry-tasting beer and one with a lot of unfermentable sugars with a rich, sweet personality, as in a doppelbock.

The chemistry becomes vastly more complex when we involve living creatures to ferment our beer. As their physiologies are exquisitely sensitive to temperature, this offers another important control point. As kinetics would suggest, yeast operates more enthusiastically at higher temperatures, but this is only partially a good thing for beer. The yeast has a lot to accomplish, and each of its many activities involves a multi-step pathway with many intermediary chemicals. Some, like esters, are pleasantly fruity and central in top-fermented beers. Others are not so pleasant or desirable, meaning it’s not a good idea to crank up the heat to get your beer in a hurry. In its preferred temperature range, each yeast will take its time, releasing fewer of these bad-tasting byproducts and do a better job of cleaning them up after fermentation. This is what beer conditioning is all about. Lager takes this to an extreme, with yeast at the very low end of their cold-tolerance, with a long, chilly conditioning. No wonder its flavors are clean and smooth.

It is believed that seasonal temperature management is what inadvertently led to lager. When the Bavarians, as many countries did, banned the brewing of full-strength beer except in the cold half of the year, they created conditions where a cold-tolerant hybrid yeast species could thrive. As a general rule, early lagers were conditioned in cellars over the summer to be enjoyed in the fall, while brewing of weak “small beers” for hydration continued in the warm season.

OK, it’s beer. Now what?

The unfortunate truth is that beer is an unstable product, absolutely not ever in a state of equilibrium. So, from the moment it’s packaged, it starts to change. Even at room temperature there’s still a lot of heat energy available for chemical reactions, which is why beer stales four times faster when not refrigerated. It’s also acidic enough to encourage other reactions like the breakdown of fruity esters. Alcohol itself is plenty reactive, and certain oxygen-bearing molecules work their dark magic, creating stale, papery flavors.

The lesson here? Check those freshness dates. Most beers are good for a month, then slowly decline, with both the lightest and the hoppiest beers aging most quickly. “Best by” dates for imports are often a joke. A golden lager is not “best” at a year old, or even six months.

Why is cold beer so attractive?

Even though for most of us refrigeration is ubiquitous, there’s a cultural memory from the time when cold could only be provided by ice. In hot weather, this was a genuine luxury. Even today, it retains its soothing charm.

Prior to modern times, every effort was made to keep beer as cool as reasonably possible. In Britain, this simply meant keeping the beer in the cellar and drawing it up to the bar with mechanical “hand pumps.” In the best circumstances, this kept the beer below about 60 °F (16 °C). In a moderate climate, this is plenty refreshing.

At these higher temperatures, though, beer can hold perhaps half to two-thirds of the carbonation typical of beers served ‘cold,’ which is generally held to be 38 °F (3 °C) for lagers and similar light-bodied beers. British cask ales are low in alcohol and relatively light in body. As carbonation has been shown to mask other flavors, cask ales show more malt and hop character—and they’re brewed for this as well. It’s a great example of how clever people adapt to technological limitations to create beers that work perfectly within those limits, sacrificing nothing. Their lack of gassiness and light bodies make them the perfect session beers, enjoyed in large servings.

Carbonation is simply carbon dioxide dissolved in a liquid. There can be quite a lot—in beer, as much as two or three times the equivalent volume of the liquid at atmospheric pressure, depending on temperature and pressure, with more CO2 dissolved at lower temperatures. When you pop the top off a bottle or can, the lowered pressure allows the gas to gradually leak out.

In very weak beer, the numbing chill in your mouth can be one of the strongest sensations along with wetness (yes, there is a wet “taste”) and the tangy prickle of carbonation. The lightest beers, as seltzers and sodas do, lean on these attributes for much of their impact. When the chill goes away, so does the carbonation. At that point, the flavor system pretty much collapses. To keep the flavor coming, drink quickly.

The Brazilians have both a lot of warm weather and very dilute mass-market beer. They’ve solved the problem by serving their chope draft beer in little ten-ounce tapered pils glasses, very, very cold. They give each beer a fillip of dense foam produced by a “creamer” faucet, a long-lived visual reminder of the carbonation that was present when the beer was poured.

A bartender pours an ice-chilled “chope” draft at Pinguim Cafe in Riberão Preto, Brazil, a town long famous for breweries.

“Drinkability” at one point was simply an excuse for beer thinned out with adjuncts and extra water. Although you don’t hear much talk about it, this concept remains the cornerstone of all mass-market beer today. I’m not necessarily knocking it; some people just want to drink a lot of beer in a session, and it’s nigh impossible with IPAs and other big styles. Even with craft- and quality-minded enthusiasts, there’s a lot to be said for the easy drinkability of classic lagers. We see it in our pubs: people start with an IPA (or a double), then switch to something less chewy.

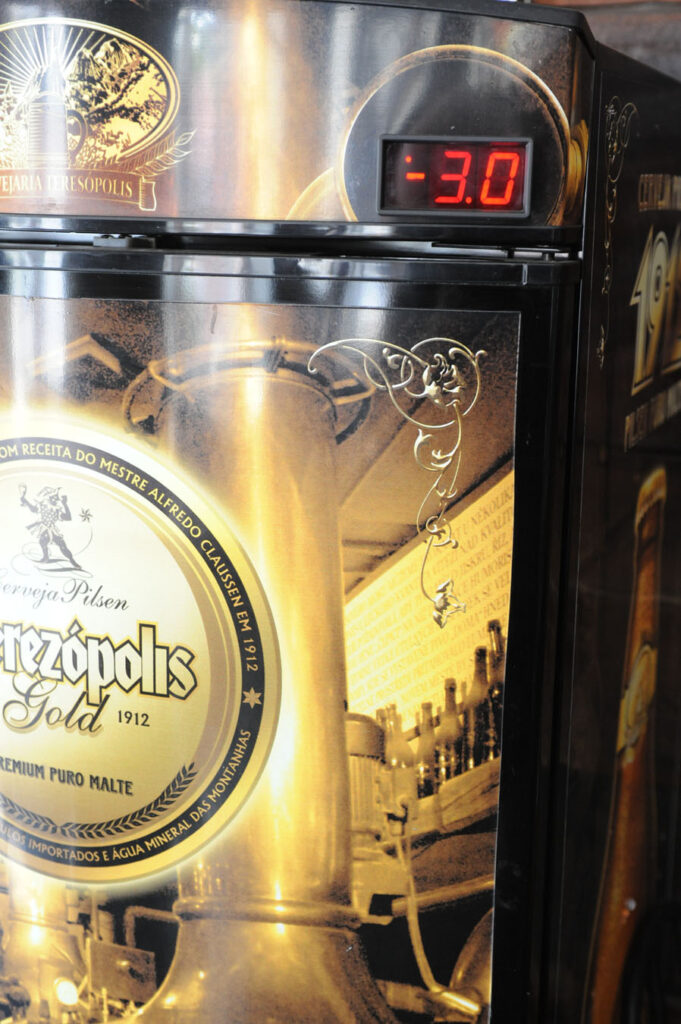

Temperature readout on a draft beer chiller in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. That 3 °C translates to 26.6 °F!

If you’re drinking to keep cool, I have to say it’s not a very effective strategy. In addition to raising your body temperature, alcohol is also a diuretic, drying you out when you need to be hydrating. With less water in your system, you sweat less and are less able to regulate your temperature. There are various strategies for managing this. Mexico has a tradition of beers with additives like tomato and lime juice, often topped off with salty-spicy seasonings like Tajin®, which replace electrolytes and encourage sweating. And as my editor told me, “Living in Bangkok, I never thought I’d enjoy drinking pale lagers like Singha poured over ice—but sitting outside on a hot night while eating some spicy street food, that is just the thing.”

As fall approaches, there’s a long tradition of darker, richer beers, such as the märzen and Vienna. The toasty Düsseldorfer altbier seems to have descended from erntebier, or “harvest-beer.” It’s hard to scientifically explain, but these seem to go better with the chilly days and the richer foods of the season.

There is still a tradition of “winter warmers” in Britain, although the term is forbidden on packaging in the U.S., because it implies, er, um, something physiological?—and we can’t have that. Still, strongish dark ales are generally the template for holiday ales, whether spiced or not. They do taste just right when there’s a nip in the air.

In the coldest months, there are warmed beers—or at least there used to be. In the days before central heating, the quickest way to warm up was to pour hot liquid directly down your gullet. Spiced beers, often spiked with spirits or fortified wines and enriched with eggs and cream, were the original “nogs” and can be quite tasty on a cold day. They’re fun and festive, with a lot of surrounding culture. Search for flip, “yard of flannel,” syllabub or lambs-wool, and see what turns up.