© 1996, Randy Mosher / All About Beer Magazine

In early 1995 I was approached by the legendary Ralph Olson of HopUnion with a proposal: If they financed and arranged a trip to cover the hop harvest, would I be willing to make the journey and write a feature for All About Beer magazine, who had agreed to run it? I jumped at the chance, as I couldn’t pass up this opportunity to visit four important hop regions at harvest time and talk to the people who were making it happen. It turned out to be a fun article.

I was gratified the next year when it won the North American Guild of Beer Writers award for best feature article. It was illuminating for me, and I hope you’ll feel a bit of the spirit of being there.

My everlasting gratitude to Ralph Olson and the small-brewery specialist, HopUnion, now merged into Yakima Chief Hops. The article is serialized here on four pages, by region.

To lovers of great beer, hops are a magical ingredient. Capable of taming the sweet excesses of the most toothsome malts, and of adding an ethereal aroma to lagers as well as ales, hops are beer’s perfect herb. For those of us who cherish the hop, the attachment only grows stronger with time.

For the people who live with the hop, and lovingly coax it out of the ground, the bond is even stronger. Steeped in tradition, hops have long intertwined themselves with the lives of their caretakers. A petulant crop, hops can be at once infuriating, intoxicating, and incredibly rewarding. Growers everywhere imbue the hop with a powerful personality—sometimes sadistic, sometimes beatific, always captivating.

SAAZ – CZECH REPUBLIC

I am met in the Czech Republic by Richard Mattas, Managing Director of Czech Hops Worldwide, the HopUnion affiliate there. As he whisks me off toward the hop region, we first stop at Plzen, about an hour south of Prague. At the Pilsener Urquel brewery we quickly ditch the tour and duck into the brewhouse. There’s a cart near the kettles holding a can of tarry hop extract and a bag of sharp-smelling pellets next to the more traditional Saaz aroma hops.

The rolling Czech countryside reminds me of Kentucky, but dotted with little fairy-tale villages. We pass a cement plant, which, I will later learn, is the source of raw materials for the dumplings in certain of the country’s restaurants.

The hop fields of Zatec (say: ZHA-tetsch), better known to us as Saaz, are our destination. On the farm, the harvest scene is similar to that of Yakima—a brisk, controlled pace. Hop-laden carts are being pulled by tractors through the squishy orange Goldbach Valley mud, the iron content of which is essential to the unique aromas of Czech-grown Saaz hops. The hops display the beautiful reddish streaking on the bines (vine stems) that earned them the name “red bine.” The picking machines are smaller here than in Yakima, but are otherwise quite similar. The unfortunate plants are strung up and stripped, the cones cleaned, kilned and baled. Special emphasis is placed on the certification process, with tamper-proof seals and serial numbers, which will later be authenticated by beautiful, engraved documents resembling stock certificates.

Dormitories sit next to the picking center, housing for the student “Hop Brigades” that come to help at harvest and in the spring. On the way into Zatec, Richard gleefully honks, startling groups of people stealing corn from local fields. In town, he whoops his car alarm at a couple of attractive young women. I’m starting to understand why his counterparts at HopUnion Bavaria call him “big boss of Czech Republic.”

Zatec is beautiful town, evidence of the incredible prosperity hops provided in earlier times. Times have been hard in the last century, but are improving. The region has been drained by the whims of foreign domination: Austria-Hungary, then Germany, then the Soviet Union. It is finally awakening with a hell of a hangover, energized by potential, but stymied by the chicken-and-egg problem of starting the business cycle without available cash.

The core of Zatec is an oblong walled town dating to 1265, the year the city was chartered. The town square is ringed with houses of that vintage, whose basements, with their Gothic walls and vaulting, were once at ground level. Seven hundred years of compacted pocket lint have raised the streets to their present level. This inner core is ringed with hop warehouses and spectacular villas once owned by prosperous hop merchants. The refurbished estates exult in fresh, characteristically Czech cake-icing paint jobs.

At one end of the walled town, in the former castle, sits the Zatec brewery. It too needs some work, but has fared as well or better than some US breweries of similar age and size (New Orleans’ Dixie comes to mind). A handsome 4-vessel copper brewhouse starts the brew. From there the beer heads underground through glass piping to galleries hacked from solid rock, chilly and dripping. Primary fermentation is in shallow open squares; the beer then descends to epoxy-lined lagering tanks. At the very bottom, at the base of the castle wall, is the brewmaster’s office. A heavily-barred window looks out onto a tangle of wild hops.

We have a taste of the beer, passing around a huge copper tankard, and discuss the David Copperfield show on TV the night before, the one where he “disappears” the Statue of Liberty. “I think it is a trick,” the brewmaster says, and everyone agrees. I tell him that he is not our greatest magician.

The beers form a close-knit family, typical pale Czech lagers in 10°, 11° and 12° Plato (an indicator of strength) versions. The first two are all-malt; the 12° is boosted with sugar. All show a clean maltiness, a firm bitter finish, and an enormous spicy hop bouquet.

The brewery had been slated for closure, but was recently bought by an independent investor, who has spruced the place up a bit. As we leave, Richard points to a bicycle by the front gate: “That is the brewmaster’s car.”

Across town is the Czech Hop Grower’s Union, a massive concrete communist-era prison for hops, in fact the world’s largest. Richard is nervous and doesn’t want to be seen wasting the director’s time, and he grills me to make sure I have appropriate questions before we go in. Franticek Chvalovsky, the director, gives us a bit of a history lesson. “We start here with tradition: a thousand years of Czech hop plants, which did not happen by chance. Of this we are very proud.” Authenticity has always been, and still is, carefully guarded. “The high point of this protection was in the 14th century, when Charles IV banned the export of hop seeds upon pain of death, an extraordinary measure.”

“Saaz hops have their own character, especially the fine aroma, not attainable by other hops in other regions. Les Roy has three hectares in Moxee (near Yakima). No results.”

“Here in Zatec, our destiny is hops. But, we have to admit that the age of the all-powerful brewmaster is dying off. On one side brewing is just business, and they know that if they brew light beer they will sell more to women and kids. I think light beer is comparable to Coca Cola.”

“I wish you in America to keep in mind that here are the people who love the hop, who love good beer. ” He pauses. “I think the people in the states would also like good beer.” “We’re trying, ” I say, and he laughs sympathetically.

We move along to the Zatec Hop Research Institute, to meet with Professor Vaclav Fric, the godfather of just about every hop planted in the Czech Republic today. Hops are the subject of research everywhere, as scientists work to come up with high-yielding, disease-resistant plants with fine aroma. It’s challenging, but new varieties are released every year.

“In the late 1950s,” he explains, “there was not much interest here in hybrid research; there was plenty of work to do to just save the original material here. But it eventually became clear that if we did not change the genetic base by pursuing hybrids, it would be impossible to make any more improvements.” Those are evident in the recent release of a number of new varieties, especially the Sladek and Bor, highly bitter hops with good flavor characteristics.

Another important line of work is what Prof. Fric describes as a “deep process of revitalization,” the propagation of virus-free stock. Viruses are endemic to hops. They sap the plants’ strength, which results in lower yield and makes them more susceptible to disease and pests. By propagating the plants from the meristem, the microscopic tip of the growing shoot, virus-free plants can be produced which yield 150-170% better than conventional ones. No one knows how long the plants will remain virus-free, but some have gone five years with no signs of re-infection. “The growers,” he beams, “are fantastically satisfied.”

The Institute has a fully-automated pilot-brewing facility, and Prof Fric has gone to fetch us some beer from their research stock. “Imagine,” Richard whispers to me, “being served a beer by Professor Fric!” The beer, as expected, was pure nectar. “We brew strictly to Reinheitsgebot (the German beer purity law) here. We don’t go for that extra-yellow color. We like it a little darker—the Plzen style.” The professor also values other properties of the hop: “It is a sedative, and it supports digestion. All the beer drinkers look like me—healthy!” I myself am starting to feel a healthy glow.

We stop at another farm, a large place formerly a mixed-crop cooperative, an odd mix of art deco stucco and communistic gloom. The pace is slower here, maybe a little too slow. Inside, in every room, on every table is a loaf or two of bread, and young workers are passing out the mid-afternoon snack, a tasty spread of fresh cheese mixed with onions and sweet red peppers. The walls are covered with girlie pictures; one shows a naked babe lying in a pile of hops which would look so cool in my basement. On the desk sits a great bulky telephone and a flyswatter big enough to give a rhino a concussion.

Outside, a worker pounds desperately on a broken truck axle. Richard is not happy. “See, no hops!” The picking machine is idle, at least for the moment, as delays on another farm have thrown things slightly off-schedule. He sweeps his hand around, “This is socialist agriculture.” He curses. “It’s a war.”

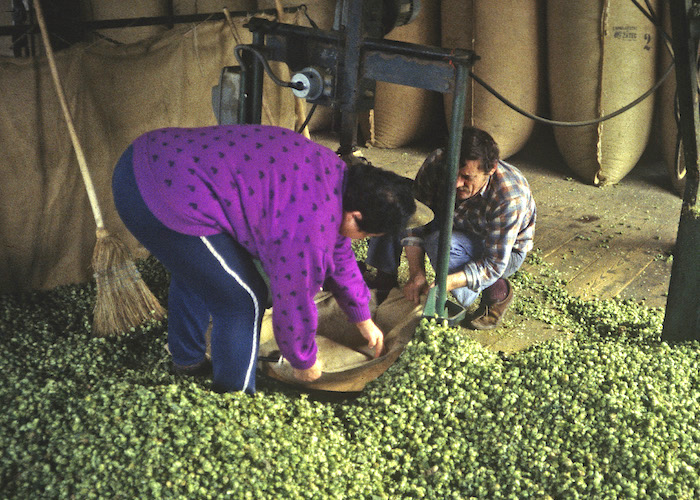

Below, top to bottom, left to right: 1) A load of world-famous Czech Saaz hops trundles off to the picking plant. 2) Workers at the hop processing plant fit a burlap bag or “pocket” into the baler. In the old days, the hops were stomped into the bag by a person. Note filled pockets along the back wall. 3) Brewers leveraged Bohemia’s longstanding excellence in glassblowing to make highly functional sanitary piping.