© 1996, Randy Mosher / All About Beer Magazine

In early 1995 I was approached by the legendary Ralph Olson of HopUnion with a proposal: If they financed and arranged a trip to cover the hop harvest, would I be willing to make the journey and write a feature for All About Beer magazine, who had agreed to run it? I jumped at the chance, as I couldn’t pass up this opportunity to visit four important hop regions at harvest time and talk to the people who were making it happen. It turned out to be a fun article.

I was gratified the next year when it won the North American Guild of Beer Writers award for best feature article. It was illuminating for me, and I hope you’ll feel a bit of the spirit of being there.

My everlasting gratitude to Ralph Olson and the small-brewery specialist, HopUnion, now merged into Yakima Chief Hops. The article is serialized here on four pages, by region.

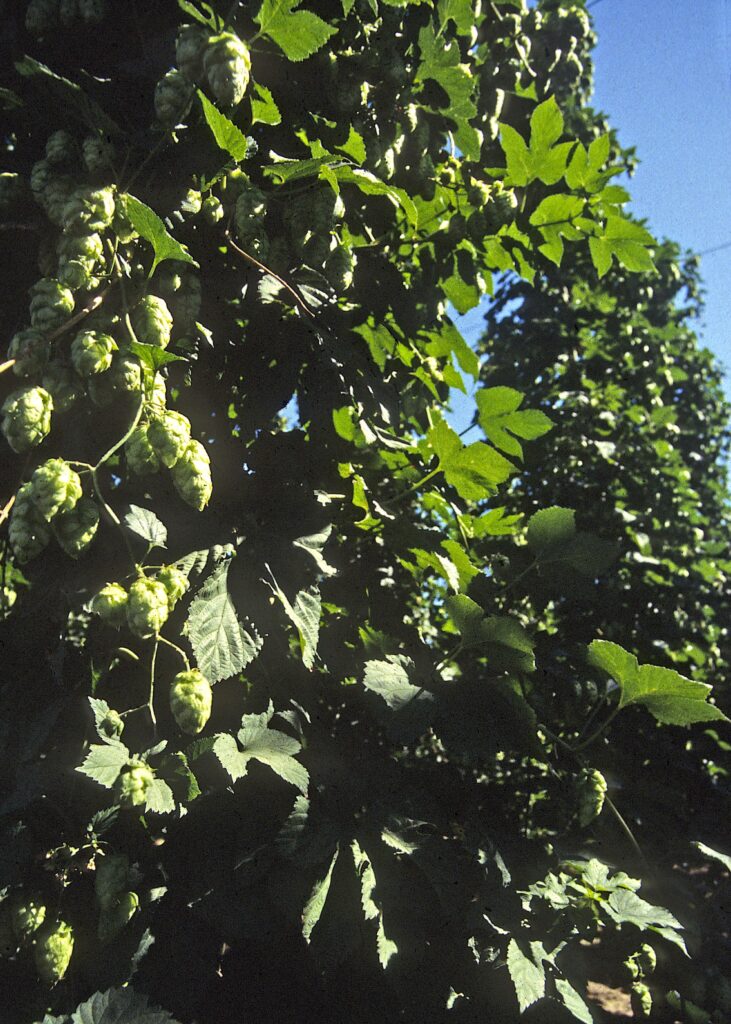

To lovers of great beer, hops are a magical ingredient. Capable of taming the sweet excesses of the most toothsome malts, and of adding an ethereal aroma to lagers as well as ales, hops are beer’s perfect herb. For those of us who cherish the hop, the attachment only grows stronger with time.

For the people who live with the hop, and lovingly coax it out of the ground, the bond is even stronger. Steeped in tradition, hops have long intertwined themselves with the lives of their caretakers. A petulant crop, hops can be at once infuriating, intoxicating, and incredibly rewarding. Growers everywhere imbue the hop with a powerful personality—sometimes sadistic, sometimes beatific, always captivating.

HALLERTAU – BAVARIA, GERMANY

Change is occurring in all of the world’s hop regions, but is most dramatic in the largest of those, the Hallertau of Bavaria. Hops are still grown in “gardens” here, with an average size of about 15 acres, despite the fact that there are over 43,000 acres in cultivation. Today there remain just one-eighth the number of farms as in 1900, despite the ten-fold size of the harvest. This consolidation, which will continue into the future, is having a dramatic impact.

Many factors are at play here. Some, like the increasing reluctance of the younger generation to take up the farming life, are common to all farming regions. Others, like the commoditization of the bittering hop, valued solely for its content of bitter resins, are unique to the hop world. Increasingly, for smaller, older, or more casual farmers, the amount of effort required to grow hops seems not worth the reward.

Hops are a high-maintenance crop. As the Hopfenbaueren (hop farmers) say: “The hops must see their master every day.” Formerly, their value as “green gold” was unquestioned. Everywhere I went, I saw evidence of past prosperity, but old days when a small garden of hops could supply a pot of ready cash are long gone. Hop cultivation is increasingly being concentrated in the hands of the serious growers who make a specialty of hops.

We are zipping through the manicured Bavarian countryside, on our way to visit such a grower. I am escorted by Sebastian Heimeryl, head of the HopUnion facility in the village of Au, in the heart of the Hallertau, about an hour north of Munich. Also with us is his daughter Simone, who is apologizing for her English, excited to have a chance to hone her skills. Lush hop fields, deep pine forests and tile-roofed villages whip past, alternating briskly. Each town is announced by a Maibaum, a tall decorated pole, the forerunner of our Rotary Club-bedecked welcome signs. Along with the symbols and crests of butchers and bakers are images of personal computers and insurance company logos.

We pull into a neatly groomed farm and stop in the courtyard. Simone says “Wait,” and nervously looks to make sure that the chain belonging to the menacing-looking German Shepherd is attached to something solid.

The farm belongs to Bernhard Wernthaler, an energized man who is the Hopfenbauer of the future. Now in his prime, he appears more mellowed than hardened by his years in the fields. Far from the exhausted resignation of some of the older growers nearing retirement, Herr Wernthaler seems boundlessly optimistic about his place in the future of hop-growing. He has been to Yakima, and he has seen The Light. His pride and joy is his picking machine, upon which he dotes like a kid with a custom hot rod, tweaking every little mechanical thing in search of better performance. The reward—for leaf and stem content half the average—is a better price, thanks to a newly-instituted policy that offers a bonus for hops of above-average quality. As grandma sweeps up the courtyard and his diesel generator hums in the background, he assures us: “My family will be a hop family in the future.”

A short distance away, we stop at another hop farm. No dog check is needed here, as there are already strangers in the yard. This is a large farm, and a number of farmers have brought their hops here to be baled, weighed and certified by the government official who has set up shop here in the garage. An electronic scale connected to a laptop computer records the weights and serial numbers; serious-looking certificates whirr out of a laser printer. Bags are stenciled and finished-off with that most ancient of guarantor of authenticity, the hot wax seal. As I watch, one of the farmers points to a bale and says: “The hops here are not so good as in the bottle.”

We are making the rounds, pressing the flesh. As we do, purchasers from the merchants, Hopfenschmussers (literally, “hop-lovers”) are doing the same. “This personal contact is very important,” says Simone. The hop community here is quite close-knit, despite being the world’s largest. Growers are free to sell to any of the dozen or so hop merchants, or even directly to the brewers; establishing personal relationships is the best way to maintain a reliable supply of the best hops.

We spend a little time in the hop museum in Wolnzak. If there was any doubt, it is now crystal clear that the hop is thoroughly integrated into the cultural and spiritual life of the Hallertau. Fields are blessed by priests in the spring, and Thanksgiving ceremonies are held each fall in the churches. As recently as 1980, the Pater of the Kloster Altstadt went from farm to farm begging for hops to be used in the monastery brewery.

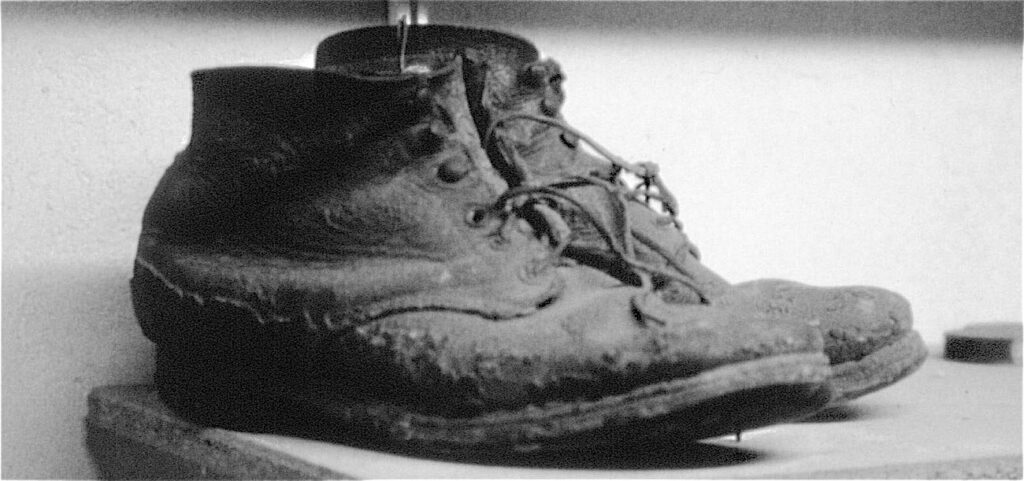

A pair of resin-covered shoes sits on a shelf, the primary tools of the trade for a Hopfentreader, the man who jumped inside the hop sacks and literally tread upon the hops, compacting them into tight bales.

Among the tractors, photos, and picking baskets are pieces of brewing equipment once used on a hop farm, and the director casually mentions that there are still a few such farmers still brewing. My homebrew heart starts to beat a little faster.

At another farm, harvest is carried out without much joy. This is a small farm, and things are hard. The owner is 55, and would quit farming altogether if he thought he could find a job at his age. His children have chosen non-farming lives, and he seems happy for their success, but the weight of ten more years of farming weighs heavily on him. As we discuss the hop and its unusual hold on people, he grabs a plant and rubs the rough leaves on my arm. “There,” he says. “Now you have been touched by the hops. They will never let you go.”

Things turn technical the next morning, when I find myself in the presence of Dr. Johann Meier, Director of the Hop Research Institute at Hüll. This place is the nexus of all progress in the German hop industry. Research is conducted into cultivation, plant protection, analytical methods and breeding of new varieties; marketing and advertising for the hop industry also come from this institution. Nearly half the varieties of hops in Hallertau were developed here: Perle, Spalt Select, Hallertau Tradition, Magnum, and the new high-alpha variety, Taurus.

Another function of the Institute is to detect misrepresentation of hop varieties by conducting chemical analyses. “I do not like this work,” he says, “We are researchers, not police.”

A walk down the hall reveals labs filled with high-tech equipment as well as fish tanks used as ladybug ranches. Out on the grounds are greenhouses and a small conference center, complete with its own little bierstube, as well as experimental hop gardens.

At the edge of their property, I spot a large yellowish building with the familiar eagle-draped “A” of Anheuser Busch. I ask Dr. Maier how they are as neighbors. “Very good neighbors.” he says. August Busch III personally visits the 60-acre A-B farm every year. They are a very large purchaser of German hops, so much so that “They want a certain direction, and we follow it.”

I ask him what he thinks of their beer, and he replies: “People here say that it is not so good. But in fact it is a different beer. And when I am in America, I find it quite easy to like this beer. But to my taste, it is not bitter enough. I often talk with Busch and his brewmaster about putting more hops in it, and they say the market won’t allow it.”

The next stop is in Mainburg, for the Hopfenbonitierung, a formal judging of this year’s hop crop. The room is packed. Dozens of purple, hop-filled bowls are lined up on the floor, and a row of judges runs through the middle of the room. There is much sniffing and intense discussion among the judges—farmers, hop merchants, and others with a good nose for the hop.

The event director is surrounded by a knot of local reporters. He is happy to report to them that this year’s crop is a good one, of good quality and average quantity. “But the average here is quite good. We are lucky after last year, when the quality and quantity was not so good,” a bit of an understatement.

Simone informs me that she has contacted the homebrewing farmer and that his place will be our next stop.

We are warmly welcomed into a small stucco building with a quaint and crusty look. A sign advises us that this homebrewery was built in 1900, although the present kettle dates only to 1926. Half a level up is a small, angular copper kettle, set into tile just like a commercial brewery. Near the ceiling is the coolship, a shallow pan in which the hot wort, or unfermented beer, is cooled before fermentation. A rectangular, wood-insulated lauter tun sits off to the right, positioned high to take advantage of gravity. A small door leads to a low, closet-sized chamber, the Gärugskeller, or primary fermentation room. It holds a bathtub-sized open fermenter, with room for nothing else. Directly below this is the Lagerkeller, where beer is matured at cool temperatures. It holds three small industrial-looking tanks of about eighty gallons each; one of them appears to be made from cast aluminum.

He offers us samples of two lovely beers, both unfiltered drafts directly from the lagerkeller. One is an apple-ish Helles (light), enthusiastically hopped with four ounces per five gallons of fresh Hallertau hops. The other, which he describes as a dunkel (dark), is a medium-amber beer with a subdued toasty edge. With an incredibly creamy head, it starts out quite malty, then finishes refreshingly crisp and dry. To my homebrew taste, these are the best beers I tasted in Bavaria.

He has been brewing since 1956, and proudly shows off his award certificate, won in a national competition of German homebrewers. Since homebrewing in Germany requires a special license, the number of homebrewers is quite small, although if this man’s beer is any indication, highly skilled. “The beer has to talk to you,” he says. “It must say ‘come here, have another.’”

I lurk around in a homebrew-induced rapture as everyone else converses in Bavarian dialect. I scribble “Höfbrau Himmel im Bayern” (Homebrew heaven in Bavaria) in my notebook, and show it to Simone, who nods in agreement.

Evening finds us in the Bierkeller of a 500-year old castle brewery, the Schloss Bräuerei von Au, still in the hands of the original noble family. It is a mix of ultra-modern manufacturing and time-worn rustic charm. Parked outside is a big BMW with two novelty license plates in the back window arranged to say “HOLLEDAU LÖWEN (Hallertau Lion).

Our dinner companions cause a stir when they arrive, as they are dressed from head to toe in 1850s Bavarian farmer regalia. These two couples, one middle-aged, the other somewhat older, belong to a group concerned with preserving Bavaria’s culture and customs. They affirm the role of the hop in traditional culture as they talk of hop harvest season: a festivals, parades, singing, dancing, and a hop picking competition. Of course there was a queen, a young lady whose life would often be changed dramatically by the celebrity and new self-confidence. Before arrival of mechanized picking, harvest time was a bit of a working festival, when people from as far away as South Bavaria and Bohemia would come to pick hops.

They would often find romance as well, or other connections that would enable them to stay in this prosperous area. Word of a wagon-load of girls arriving to pick hops would spread wildly, attracting boys from all over the neighborhood. An old song tells of a poor hop-picker wooing a local maiden: “Look at me! I have a true heart and strong arms. It’s all I have, but I love you.” Boy gets girl in this story, as often happened in real life.

The festival atmosphere of hop-harvest may be gone, but the sense of community is still intense here. And although MTV jostles for a place at their cultural table, interest in preserving the best of the past and the cozy Bavarian lifestyle has never been stronger, and folk life groups are flourishing.

They asked me what I thought of their world, and I told them, “To me it seems like you are living in a beautiful park. You have figured out exactly how you want to live your lives, what you like to eat, to drink. You seem so completely comfortable with everything, which is something we don’t see often in the States.” They seem comfortable with that assessment, too, and we hoist a beer for a final Prost. I didn’t mention that I felt all this comfortableness just a bit stifling as well.

As we all rise to leave, one of the men shows me his boots, which have a squeezebox-like corrugated section at the ankles. “Look.” he says, “These are old. Six hundred marks ($450) for a new pair. Only two makers left in the entire country.”

I awake at 4:45 a.m. to catch a plane and find Bavaria doing its quaint folk dance right in my stomach.

Below, top to bottom: 1&2) A “hop-henge” of Hallertauer hops ready for harvest. 3) Hops in the gently rolling countryside of Northern Bavaria. 4) The well-used Hopfentreader shoes in Wolnzak’s hop museum.