© 2019, Randy Mosher

Above: An array of tapas tempts passersby.

An invitation by the ACCE (Asociación de Cerveceros Caseros Españoles), Spain’s homebrewing association, to give a presentation at their annual convention in Bilbao provided my wife Nancy and I an opportunity to explore Northern Spain.

The homebrew conference was like they all are: lots of thrillingly geeky and enthusiastic brewers looking to exchange information and enjoy each other’s company—and beers, of course.

Bilbao is a lovely town with an old city center about a mile square that is the perfect size for strolling and sampling. Across the Nerbioi Ibaia river is the “new” town with more of Victorian feel. Further downriver are steel mills and other large industrial facilities that are slowly being reclaimed into more cultural sites, such as the Guggenheim art museum, famously designed by American Architect, Frank Gehry.

Nothing really prepares you for the onslaught of creativity, ubiquity and creativity of tapas, or pinxtos, as they are known in Catalonia and Basque country. In the entire ten-day drip, I think we only had two sit-down coursed meals. Each dish is just a few bites, and it’s always easy to find another when you’re ready. The upstairs of the city’s food market was an explosion of small bars selling these. The famous Spanish jamón is prominently featured, as are olives, peppers, cheese, vegetables and more, usually perched on fresh and crusty bread, like little open-face sandwiches. Some places, like the vermouth bar we visited in Barcelona, featured artisanal tinned seafood, another unique art of the Iberian peninsula.

Nothing wrong with the Spanish food served in America except it lacks the easy, casual vibe and small, inexpensive servings of the real thing in Spain.

Above, top to bottom, left to right: 1) Guggenheim Museum Bilbao 2) Pinxtos (tapas) at the public market in Bilbao. Note that these are just the selections available at the olive bar! 3) A giant “blossom” of fried pork belly strips on sticks at the same market. 4) Artisanal tinned fish is a world apart from the canned tuna we find on our grocery shelves. Some tapas/pinxtos establishments specialize in these, and they are delicious. 5) A selection of Spanish Vermut (vermouth) in a specialty bar at the market in Bilbao. 6) Vermouth as a cocktail, as served in Spain.

Spain embraces vermouth with more enthusiasm and creativity than the Italians and French. It’s not just an additive to another drink; it’s actually a drink in its own right. It’s also used in cocktails that flips the usual script and makes it the star, using other spirits like gin (dry style) and rum (sweet) as the modifier, and are popular enough to have bartender contests on that theme. As a drink, vermouth was said to be the only alcoholic beverage grandma would allow to be consumed before church in the morning. And why not? Vermouth is plenty flavorful, but only half the strength of most cocktails.

Here’s the basics, which you may already know. Named after wormwood (vermut), vermouth is an herb-spiked wine, often with a little fortified wine and/or spirits added to get the alcohol into the 20 percent-plus range. The herbs are the same general type used in herbal liqueurs, amari and fernets—that is to say medicinal herbs as well as culinary ones, many of them quite bitter. This balances the sweetness of vermouth and any drink containing it.

Long before this trip, I had acquired some old French distillation books containing recipes for all kinds of liqueurs, bitters and vermouths. I made the four vermouths in the Brévans (1908) book with fascinating results. Once you start tearing into these old recipes, you realize they are composed of several threads: bitter roots, culinary spices, citrus notes and evergreen ones, perhaps fruity and/or floral aromas and sometimes a few eccentrics—roasted apricot pits, galangal, grains of paradise—in the mix. Once you see the formulas through this lens, it’s easier to make changes, find substitutions and move the flavor center in different directions.

The majority of vermouths we saw in Spain were of the sweet-dark type. A classic serving of vermouth starts with a typical wine pour in a wine glass, adds chunky ice and garnished with a strip of orange peel and a skewer of small green olives. The orange is an aromatically “sweet” component that takes the edge off the bitterness, while the saltiness of the green olives further enhances the sweetness by way of contrast.

For all its wonderful complexity, vermouth is not hard to make. I modified an existing c.1900 recipe based on Madeira wine for use as the house vermouth at Forbidden Root. I make up a tincture by soaking herbs and spices in vodka for a day or two, then filtering them out. The bar staff keeps that on hand and mixes together Madeira, Pineau de Charentes (grape juice, whose fermentation is arrested by brandy), brewer’s caramel, then adds about 15 mL per 750 mL bottle of the tincture.

Once back from Spain, I kept thinking about vermouth, spurred on by the bottles I brought back with me. I’m a DIYer at heart, so I whipped up a recipe after a couple of tries that tasted right to me, solidly within the landscape of the Spanish vermouths experienced.

Above, top to bottom, left to right: 1) A sign carved in the traditional Basque lettering hangs at the doorway of the cider house. 2) The 200 year-old building houses the cider house Sidreria Bodega Restaurante UXARTE sagardaogintza, in Amorebieta-Extano, the heart to Basque country. 3) Proprietor and cider maker, José Antonio Zamalloa “Txanpi” 4) Apologies for the blurry photo, but it was pretty dark in there. A long stream aimed into a glass to stir up bubbles is a hallmark of Spanish cider.

One of the homebrew conference excursions was to a “mountain” cidery in the countryside a few miles out of town in Amorebieta. This is Basque country, preserving against long odds, a host of ancient and unique cultural traditions like language and even a chunky medieval lettering style that serves as visual identifier for all things basque.

As you may have guessed, this is a very traditional place. Cider here is from unique cider apples growing in mountain terroir, giving them a lot more tannin and acidity than eating apples. Fermentation is 100 percent spontaneous, another source of terroir. The cider itself is a pale straw color with the slightest haze. Aroma is fruity/appley, with tangy, wild overtones. It’s fairly acidic in the mouth, balanced by ample tannins. Body is pretty crisp, finish is bone dry.

Despite the heritage and traditions, we heard a somewhat troubled perspective from the owner/cider-maker. Prices people are willing to pay are so low as to be unsustainable in the marketplace. Spain’s other cider region, in Asturias, is by far the larger of the two and has much more marketing power. Zamalloa felt that despite a superior and more classic product, it’s hard to get the word out, so Basque “mountain” cider has been a little left behind. If this goes as these things usually do, people will return to the classics, but only if people there reframe them in imaginative and persuasive ways.

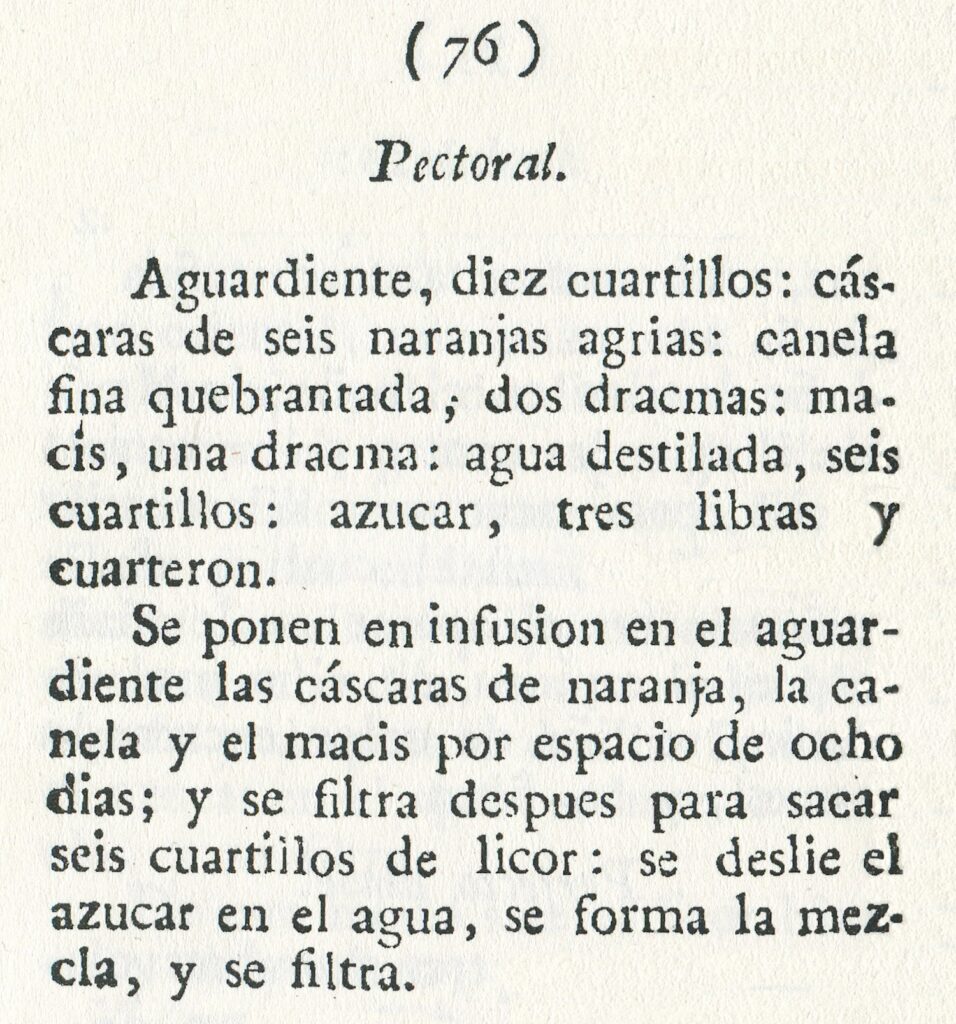

Above, top to bottom, left to right: 1) The storefront of Herboristeria Del Rei (Royal Herbalist), an ancient herb shop. The marble statue in the back is of Carl Linnaeus, the famous botanist who introduced the idea of genus and species names for living things. 2) A “Walk of Fame” style commemoration is set into the sidewalk in front of the shop. 3 & 4) Shown here is an 1824 Spanish distilling guide and a recipe for a “pectoral” liqueur. FYI, a quartillo is about half a liter; a dracma is about 36 grams; a libra equals about 3.5 kg.

We spent an embarrassingly short time in Barcelona, so I can’t give you a full travelogue. It lives up to its reputation as a unique and wonderful place. The Gaudí buildings are simply awe-inspiring, especially the Sagrada Familia, which is now more finished than not—after 140 years of off-and-on construction. If you want to see Park Güell and are coming at spring break, then book ahead or the French school kids will have the place to themselves.

A little digging identified an ancient herb shop in the old commercial neighborhood: Herboristeria Del Rei, founded in 1823. Likely Europe’s oldest, it still has much of its interior, including the original botanical paintings above the shelves. Run by a couple who must be nearing ninety, he manages the store and she consults on treatments. They sell a mix of dried herbs and more modern skin care and other products. I bought some elderflower, eucalyptus, centaury and petite wormwood, all of which are employed in liqueur recipes.

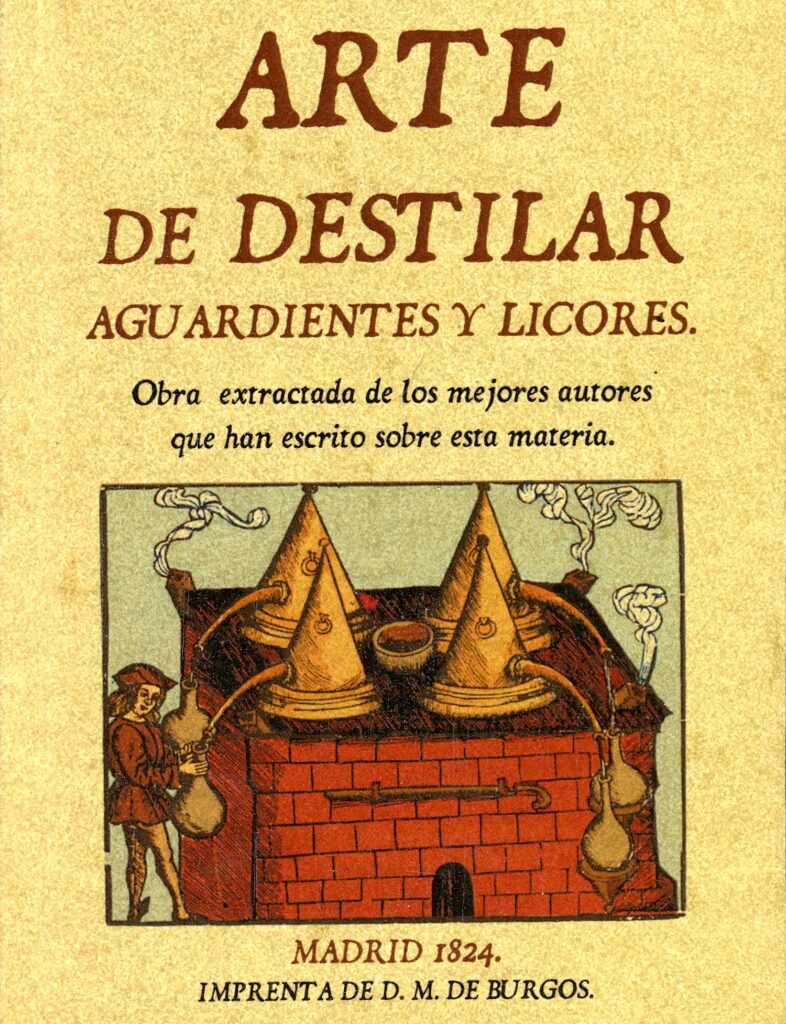

In Madrid, I found a reprint of a book that was published in Madrid in 1824, about the same time period when the shop opened. The writer must have known the shop owners, or even could have owned it himself. What’s striking about this little book is how familiar the ingredients and recipes are. When you get into herbal liqueurs, many of the recipes are centuries old: Chartreuse, 1605; Bénédictine, 1510, or so the stories go.

The recipe includes a bunch of bitter/sour orange, plus cinnamon and mace, sweetened with sugar. Except for the alcohol, it must have smelled a bit like cola, which includes those similar ingredients.

Above: Nancy and I with a group of Madrid-area homebrewers.

Madrid continued with more of the same fun, and was lively and charming. Spain has a vibrant and sensory-rich culture, and you can really feel the passion. The wine, you may have heard, is excellent. And like Italy, it is untaxed and not marked up exorbitantly in restaurants, so it’s very affordable, unlike the U.S. So, it’s a fun place to dine and drink. There’s a lot of intense research going into the wine in Spain and Portugal. Some of the most cutting edge material I encountered in writing my new (not yet published) tasting book came from Iberian researchers. As far as beer, the craft scene is still very far behind where we are in the U.S., but that’s true most places.

What’s important is to have a lot of enthusiastic and talented folks with the vision to imagine a beer culture that’s exciting as the rest of the country’s gastronomy, and ready to do the work to make it happen. The homebrewers I met in Bilbao and rejoined a week later in Madrid are exactly the place to start.