© 2017, Randy Mosher

Above: Owners of San Pascual Baylón, Nicola Capasso and Eduardo Lastra proudly displaying their benefactor San Pascual Baylón, the patron saint of cooks.

Puebla, Cholula and a return to Mexico City

This was technically another trip, but since they were close together and knotted together in my head, it makes sense to just cover it here.

The purpose of the trip was to judge Slow Beer, a specialized competition highlighting ingredients of interest to the Slow Food organization, many of which are important in its ongoing programs. Ingredients ranged from seemingly commonplace items like coffee and vanilla, but often sourced from special regions or involving unique varieties, to much more exotic items like xoconostle, black sapote, chapulines and more.

The judging took place at UDLAP, the Fundación Universidad de las Américas Puebla, the important university there. Unlike most beer competitions that take place in some generic hotel ballroom, the first day we were ushered into a vaulted wine cellar in the school’s culinary/hospitality department, which were very nice surroundings. The other out-of-the-country judge was Jason Buehler of Denver Beer Company.

The beers were better-brewed than last year, with fewer rookie technical flaws such as yeast/fermentation issues. I think the most general fault was a tendency to be timid in the use of specialty ingredients. As Jason and I have both found out in the US beer industry, when consumers see something listed on the label, they expect to taste it, without doubt. So if you’re thinking of brewing a beer to enter next year, here’s a hint: Don’t hold back.

Because of the schedule, we had a fair amount of free time to go exploring. Puebla is a medium sized colonial city less than three hours souteast of Mexico City. It is known for its particular food culture that includes a unique mole, a big round sandwich called a semita, a kind of “wet” taco called a chalupa, (I know, I always thought that was something Taco Bell came up with) and lots and lots of sweets. They have a fierce rivalry with Oaxaca over cuisine. To me, Oaxaca seems to have the upper hand, at least in terms of sheer variety, but what do I know? This will take a lot more research.

We head up to Cholula, a much older city built around an enormous pyramid with a church perched on top. We drop in on the guys at San Pascual Baylón, a one-room artisanal brewery in an industrial area.

They’re making some adventurous and tasty beers including a grepefruit IPA and a coconut American stout. They’re expanding production even as they’re complaining about the restrictions of their small space, and dream of adding a second room, or even of some warehouse space nearby.

We all head over to the Cholula Mercado, mostly filled with food merchants. It’s manageable in size, but well stocked. Slivers of an aromatic pine called ocote (Pinus Oocarpa) s being sold in small bundles as firestarters. We’re interested, as our hosts had just shared a stout incorporating it from another brewer (Cerveceria Vickers) with us. In addition to the powerful pine aromas, there are also some eucalyptus and rosemary notes—it’s easy to imagine the possibilities.

We plow through the market with our lists, asking at every stall about black sapote and flor de manita (Chiranthodendron pentadactylon), among others. The former appeared to be out of season, but I did score on the latter, an ingredient in Pre-Hispanic cacao preparations. We also bought some white sapote and xoconostle, a wild, tart relative of prickly pear fruit.

There was also quite a lot of another cactus fruit called pitaya. I confused it with the similarly named “pitahaya,’ the Asian dragonfruit, and missed the opportunity to purchase some. At any rate, the xoconostle was quite tart, with an aroma perhaps similar to rhubarb or something not altogether fruity. The white sapote turned to mush quickly, but was sweet, deeply fruity and luxuriously creamy. Maybe a beer there, also—if enough product could be obtained. As always, a lot of these unfamiliar tropical fruits defy description to us northerners.

Puebla’s old center is charming evidence of the wealth and power of the town in the 17th and 18th centuries. The old buildings go on for blocks, and there is a small neighborhood dedicated to sweets shops.

A characterful bar called “Pasita,” literally meaning “raisin,” is just off the Zócalo, or main square. They specialize in a variety of sweet liquers, the most popular being their namesake. Sweet and raisiny with a hint of spice from cinnamon and others, it is served in tall shot glasses with a toothpick holding a soaked raisin and a small cube of cheese. The cheese may seem an odd choice, but it turns out to be pure magic. The savory/salty character perfectly offsetting the super-sweet liqueur.

We head to a small bar nearby called Mazoachete run by Alejandro Cristóbal. Specializing in craft beer and mezcal, it’s a happy combination we also found in Oaxaca. We try a beer or two and small tastes of a number of different mezcals, including two variations on the pechuga technique in which a cooked chicken is hung in the distillation vessel, usually adding a certain creaminess—or possibly a chicken soup character. One of them used ostrich, and the other, lamb. Both were interesting, but the more of these exotics I tasted on these two trips, the more I became convinced that mezxcal by itself is prefection itself, and all these other things do is obscure and confuse the beautifyl smoky-fruity-cactus thing it has going on. We’d been asking all over town about mezcal from Puebla, and it’s clear that it’s a bit of a rarity in this state.

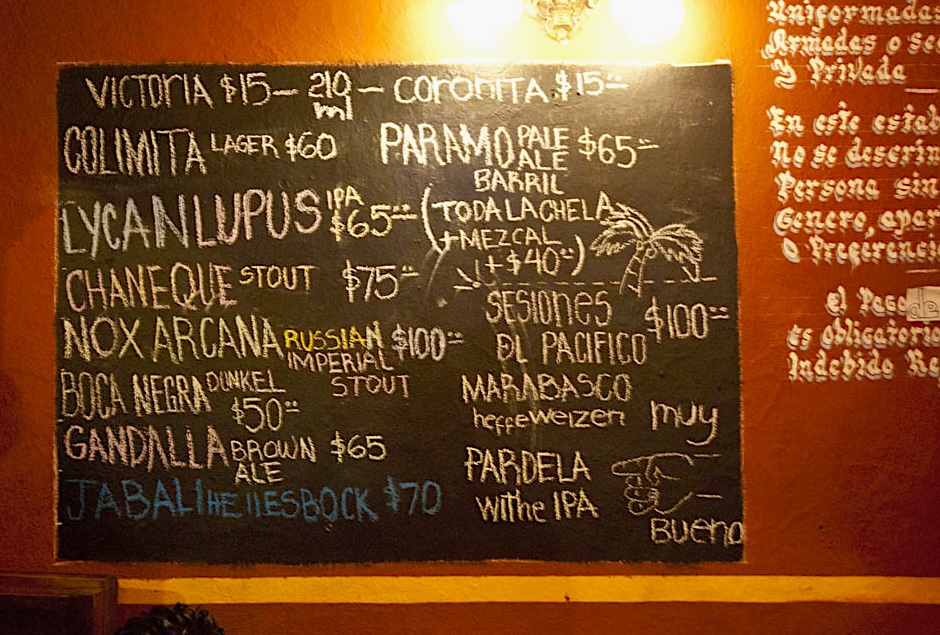

Mazomachete had a pretty well-chosen bottle list and a draft or two. The Lycan Lupus, from Cerveza Fauna, up north in Mexicalli is one of the better IPAs (say “EE-pah”) I’ve had in Mexico. Colimita is a hop-accented lager from Colima, on Mexico’s central west coast. While there’s still work to do, it’s great to see places like this popping up and drawing crowds, despite the challenges.

I was encouraged to bring my half-emptied glass of mezcal along as we walked to dinner. Lucía spotted a buñuelo dealer selling the hot and crunchy fried dough pieces with piloncillo sugar syrup added at serving. Walking along in the rainy twilight with all hands full of delightful things in equally great company was a defining moment of the trip for me.

The next day got even better. After a comically indirect cab ride, we end up at the home of Tim Knab, just across some farm fields from the Great Pyramid of Cholula

There are two parts of Cholula, actually separate municipalities, Tim says. “These people have not seen eye-to-eye since the eight century,” noting that when one town put up stop signs on the border, the other town came and took them down, and that the one-way streets meet in opposite directions, forcing drivers to divert a block to resume their course.

Tim has had this crazy career: chemist, chef, hotelier, founder of a cooking school in France and for the last couple of decades as a cultural anthropologist and Nahuatl (Aztec) language expert.

Cholula’s pyramid is the largest in the world in terms of base size and overall volume. Since they’re in a valley filled with volcanic ash, it was made from adobe rather than stone, and over the centuries it has slumped quite a bit and now resembles a natural hill more than an artificial pyramid. As we walked the pathway to the pyramid, Tim tells us to watch for bits of pottery, and as soon as we do our hands fill quickly fill with potsherds dating back a thousand years or more.

He walked us up the pyramid, through the museum and all over town, stringing it all together with amazing stories. They have a LOT of festivals in and around Cholula. Everybody gets dressed up in fanciful costumes and masks, shooting ceremonial black powder muskets, and sometimes after too much mezcal–which always happens–forget to take the ramrods out of the barrel and then people get skewered. I guess people there say “It’s not really a festival unless there’s a “muertito” (little death). Also, there a lot of feuds there, kept alive, he says, by the “sweet little grandmas.” People sometimes use the cover of the costumes and masks to shoot their enemies and then fade back into the crowd.

The area was an omportant region for the production of the priced cochineal (cochinilla) dye, evidenced by the infestation of the scaly insects on one of the nopals on the edge of the field.

It’s a lot of walking and now we’re getting thirsty—as usual. We stop into a small pulquería near the mercado, where an older gentleman presides. He fills us in on the production of pulque, the ancient fermented beverage made from maguey sap. In the back are two small oak barrels. Inside of each is the same pulque, but one of them has been sweetened.

He also sell a blend of the two. We try that one and find it not too tart for our taste and ask for a cup of the fuerte, or “strong.” It’s milky, very slightly glutinous and mildly acidic. There is a pleasant degree of funkiness, but since pulque is most often served between one and two weeks old, there is a limited chance for slow-growing organisms such as Brettanomyces to contribute a lot of wild aromatics. It’s less glutinous than some of the more commercial versions I’ve tried, overall quite refreshing and pleasant.

But our complex thirst required many kinds of quenching. Next stop was a Mezcalería down the street. They sell several commercial brands, but the attraction is a range of unbranded house mezcals. We pick up a couple of liters of tobalá, a particularly tasty wild agave variety. Mezcal is most properly served neat in a shot class, or more authentically, in a small clear glass votive candleholder with a cross embossed into the bottom.The typical accompaniment is a few half-slices of orange sprinkled with sal de gusano, a, orangish salt made with moth larvae (the same ones you might find in a bottle of cheap mezcal), chili and sea salt.

Jason buys a quart tub of their pulque, hoping for some harvesting of wild microbes for a beer back home in Denver.

We finish the Puebla trip with a live best-of-show round in front of an eager crowd at a brewpub and beer bar called Casa Don Sileno in Cholula. Just opened, it’s a nice space and the beers are fresh and tasty. IThe panel consists of myself, Jason, and Dr. Alfonso Rocha, a professor at the UDLAP school where we had been judging earlier. Top prize went to a beautifully balanced Vanilla English-style porter; second to a delightful braggot in a kind of a blond ale mode, and third to a gose made with chapilines (roasted grasshoppers) from Cerveceria Cru-Cri in Mexico City. We felt all the medal beers were genuinely deserving.

The next day in Mexico City, after stuffing ourselves with barbacoa, we hold a workshop in which Jason and I present some information about our breweries, beers and how we go about conceiving and developing them. There is a lot of good discussion, despite the dismally gloomy light in a former disco room of what is perhaps one of the world’s stranger brewpubs, the Beer Factory. Located in a former paper factory, it’s macabre in a steampunk kind of a way.

Despite the gloom, the house beers—all classic styles—were clean and well-brewed. The guys from Cru-Cru were there, and after dinner they invite us over to their brewer near where we are staying.

Located in an 18th century rectory near an old church in the Romita neighborhood, it’s mostly one big open space covered in murals, the remnants of a local politician’s time there.

It’s a clean and well-organized brewery and owner Luis de la Reguera has big plans. We taste the second batch of their chapuline gose, and as we had wished for during judging, this new batch did indeed have more chapuline character, evidenced by a woody fruitiness and an aroma that can only be compared to fresh cigarette tobacco, strange as that may sound. They also use sal de gusano, as it provides the salt for the gose and also enhances the flavor of the chapulines

This was a fitting end to the trip. As always, I’m overwhelmed by the incredibly gracious hospitality from everyone we came into contact with, and especially Lucía, Horacio and the rest of our hosts. it’s a thrill to play a small part in Mexico’s repidly developing craft beer scene and to be able to reach out and get a great big, juicy taste of its rich culture and cuisine.

Can’t wait for the next one!

Below, top to bottom, left to right 1) Our “handler” and Slow Beer Competition Director Lucía Carillo working the numbers behind an extensive samples meant to ensure that all judges had the chance to see, smell and taste the many specialty ingredients used in the beers 2) Tim Knab is a cultural anthropology professor at the Universidad de las Americas, Puebla 3) Bundles of ocote wood at the Cholula Mercado 4) In the Cholula market, a crate of pitaya, a cactus fruit unrelated to the Asian “pitahaya,” or dragon fruit 5) Cochineal insects in their fibrous shelters feeding off a prickly pear cactus near the Great Pyramid in Cholula 6) A bar called La Pasita a few blocks off the Zócalo in Puebla specializes in sweet liqueurs 7) On the beer menu at the beer and mezcal bar, Mazoachete, near the Zocalo in Puebla you can see the extreme difference between mainstream and craft prices 8) At a pulqueria in Cholula: both barrels held the same milky base pulque; one was sweetened 9) The view from the live best-of-show judging table at Casa Don Sileno in Cholula 10) View from the brewing deck the main room at The Beer Factory in Mexico City