© 2022, Randy Mosher

Pictured above is Weber (blue) agave growing in the tequila valley, with the Volcán de Tequila looming behind.

My Forbidden Root partner has drawn me into a project to formulate and launch a line of premium 100% agave Tequilas flavored with natural extracts. To talk to distillers and get a feel for the business, we spent a few days in its heartland.

While Tequila production is allowed in adjacent parts of a few other states in Mexico, most of it comes from two main production regions in Jalisco: the Tequila valley, about an hour west of Guadalajara, and Los Altos (the highlands), about 2 hours east—Arrandas being the best known town there. Tequila Valley is volcanic soil, dark in color. Highlands is red, rich in iron. It’s not entirely clear how much difference that makes, as there are lots of other factors.

There are tastable differences between regions, although generalizations don’t always apply. Highland Tequilas are often more fruity, less green. Tequila Valley ones, more green/cactus/cucumber (aldehydes). They’re sometimes more lean and less rich and fatty, too. According to the people we talked to, differences are not simply altitude or cultivars or terroir, but to some degree are related to differences in the local wild yeast, the theory being that mango farms in Tequila Valley may offer a unique environment for the local yeast.

Above, top to bottom, left to right: 1) Unroasted agaves outside a traditional horno, or steam oven, a simple masonry box with steam inlets. 2) Autoclaves: pressure-cooker type of heating devices, with uncooked piñas ready for loading. Note the much darker cooked ones in the center autoclave. 3) A roasted agave heart, or piña, cut open for tasting. The cooking process develops quite a bit of caramel, brown sugar type flavors that find their way into the finished distillate. Note the crushing/extracting machinery in the background. 4) Open fermentation of cooked agave juice, which usually takes about three days.

Cooking is necessary to break down the agaves’ carbohydrate, inulin, into fermentable sugars via heat. There are two main cooking techniques: steam-heated ovens (hornos) and low-pressure steam autoclaves. Both produce fairly similar color/browning, but distillers manipulate time and temperature to achieve specific Maillard flavor profiles. Because the distillate is clear before wood aging in reposado and others it’s easy to overlook this rich layer of flavors. A rare few Tequila producers use pit (earth) ovens like those for Mezcal, but since these fall outside the rules for Tequila, products made this way must be labeled “agave spirits.”

Three day ferments are fairly typical. While we saw mostly ferments running at ambient temperature, some do control temperature for a lower, slower ferment to avoid runaway fruitiness. Wild yeast is sometimes used for 100% agave Tequilas, with harvest and re-pitching, like sourdough, but not always. Normally. Definitely lactic fermentation towards end of yeast activity, cap (pellicle) forms. Needs to be moved to tanks fairly soon after that to limit amount of acetic acid. For bargain brand “mixtos” Tequilas made from 50% agave with the rest of fermentables being white sugar, cultured yeast is the norm.

Most small- to medium-sized distilleries use pot stills, more often stainless, but some employ copper. In these, two distillations are the rule: first at about 22% alc/vol, the second one rectification resulting in about 110–120- proof. Obviously lots of important process variables here, including temperature and cut of heads, heart and tails. Heads more fruity; tails more fatty, to generalize. Pot stills can generally create more body than column ones, but that depends on how they’re used.

Left: Traditional copper pot stills in a Highlands distillery. The larger stills at left and center are for the first, or “wash” distillation. The smaller still on the right is for “rectifying” up to barrel proof. Right: A barrel warehouse at La Cofredía in the town of Tequila.

Column stills are more common in large distilleries as they are more efficient. One pass through gets to final high alcohol content. There’s another process using something called “diffusers.” This involves extracting the juice from uncooked agave and then cooking the juice, then fermenting and distilling. This create less Maillard browning and greatly reduce the amount of brown sugar, caramel and cotton candy aromas. Those are used for the biggest and least expensive brands. Those who know characterize them as kind of lifeless.

A good deal of Tequila is sold without wood aging, in Blanco form. Reposado or “rested” tequila may age from one to a few months, while añejo and extra añejo require more and more time, respectively. Barrels almost always used Bourbon barrels, and they tend to be used until they’re practically used up.

There’s a new-ish “joven” style that involves either blending a blanco and reposado or just a brief resting of blanco in a barrel, for a slight hint of color and a more rounded, sweetish palate. Note that “joven” in Mezcal means a completely unaged (blanco) style. Another variation of this does the aging in a red wine barrel, resulting in a “rosato” tequila with a delicate pink tinge.

For some time, there’s been a fad in Mexico for “cristalino” Tequilas: extra-añejos that have been re-distilled, creating white tequilas with a rich vanilla and brown-sugar character. Also popular to some degree in the US, demand for these products have sucked up most of the available extra añejo tequila on hand, which why they’re hard to find and astronomical in price—and will be so for a while.

Filtration, cold or otherwise, and aeration affects product character, both generally removing fatty acids for a less rich, buttery/dairy character and less oily/creamy palate—so, drier, crisper Tequila.

Tons of Tequilas on the market use adjuncts in their final mix, most notably sugar (blancos) and sugar, vanilla, caramel color and oak extract in barreled products. Many are sickly sweet and reek of marshmallow, but apparently, there’s a (big) market for that. This tends to be more true of bigger brands and celebrity-endorsed exported ones rather than smaller, quality-focused houses. There is an “additive-free” movement worth seeking out, especially, I think, for aged ones which have the heaviest adjunct use.

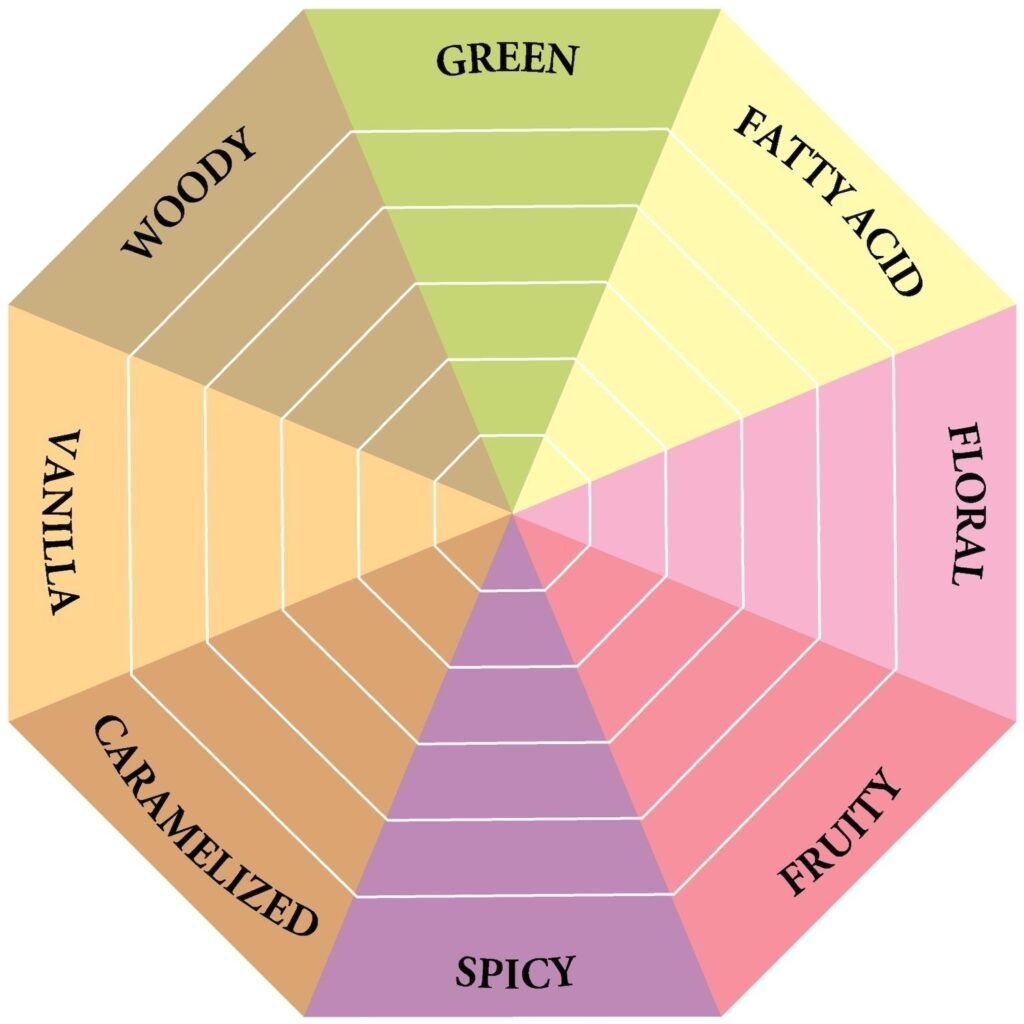

Top Left: A dizzying selection of Tequilas in a store in Tlaquepaque, an older shopping neighborhood in Guadalajara. Top Right: My personal version of a categorization of the more prominent aromas to be found in Tequila. Bottom: Barrel-shaped rental cabins dot the landscape at La Cofredía, in Tequila.

While our formal tastings of tequilas were as focused and professional as for any wine or spirit, at a restaurant in Guadalajara we were served Tequila as part of a banderita (little flag): one shot glass of lime juice (first), one of Tequila, and a final one of chili-spiked tomato juice, creating the colors of the Mexican flag.

Pondering the aromas we’d been experiencing in Tequila, I put together a flavor wheel for the elements I found most noticeable and then broke them down into subcategories. I find these charts to be a useful prompt to remember to look beyond the most obvious characteristics and dig a little deeper, based on the way flavors are created in the process. While for me, this does a pretty good job, all flavor maps are dependent on each person’s unique perceptual bubble. Your mileage may vary. Note that the “woody” and “vanilla” sectors are only important in wood-aged Tequilas.