© 2025, Randy Mosher / Craft Beer & Brewing Magazine

Everybody who creates flavorful products keeps a mental model of each ingredient and process they use. This allows chefs, brewers and others to do a kind of mental prototyping, visualizing the completed creation to quickly imagine different options until the perfect combination is found. Then, it’s simply a matter of writing it down and, oh yeah, actually making it.

It was long thought that humans had little ability to imagine flavors, but modern science has shown that not only is it possible, it’s indispensible for certain pursuits, including brewing. It turns out that imagining an aroma actually activates the brain in a pattern very similar to actually experiencing it in real life. Not everybody is equally good at this; most don’t even realize it’s possible. But it can be learned.

An important thing to know is that this kind of flavor visualization depends very heavily on the quality of the model we maintain. To be accurate and detailed, our model needs information. Constant tasting—of everything—is the way we do this. The best brewers I know make this a habit, and it shows in their beers.

It’s easy to lump all malts in particular categories together, like black or 60 Lovibond caramel, but in fact each producer’s version is different, often strikingly so, even at an identical color level. Maltsters are a tricky and secretive bunch, and they have numerous levers to pull to achieve different results by manipulating the Maillard browning and caramelization processes via time, temperature, moisture pH and others. There really is no substitute for getting up close and personal with as many different malts as you can. And as a brewery, team sensory notes on available malts should be just one more tool for the development of the next amazing beer.

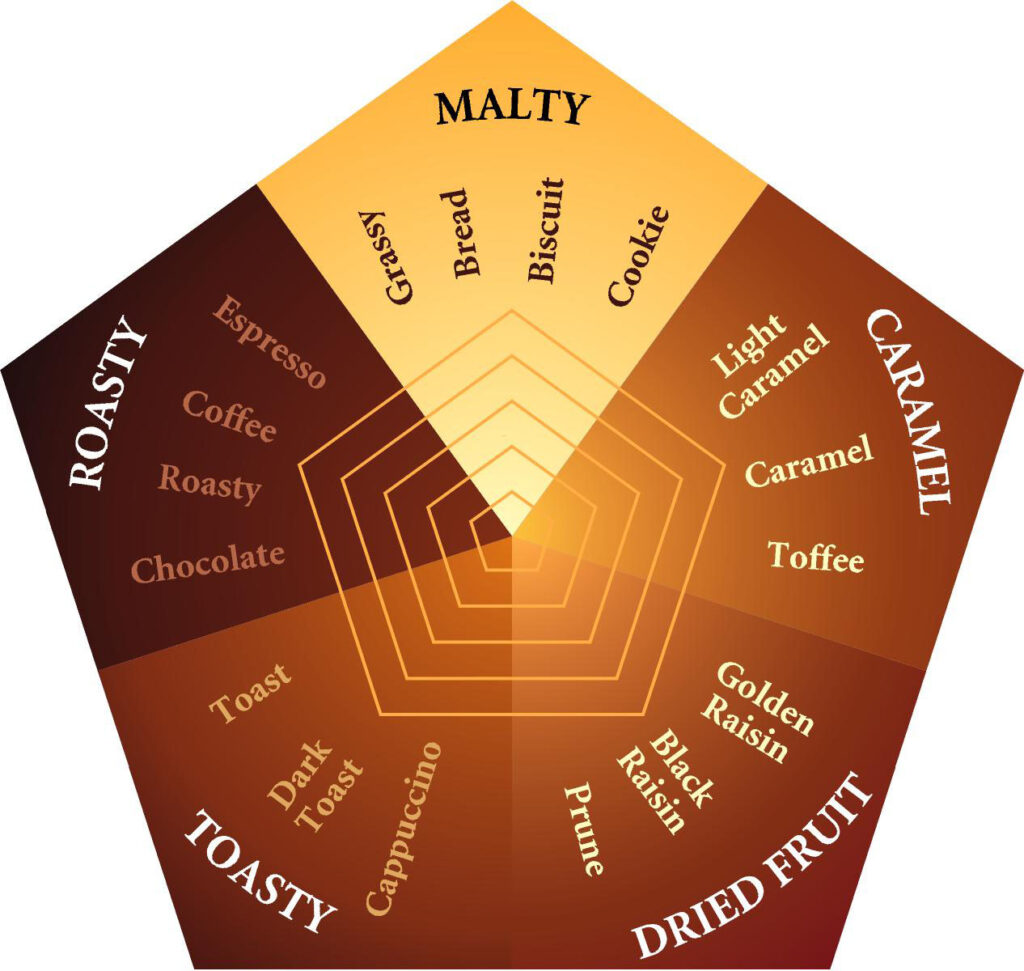

My 5-sided prism covers the range found in brewers’ alt © 2024, Randy Moshetr

Evaluating malt

The simplest way to evaluate all but the darkest malts is simply to chew on them. Human saliva actually contains quite a bit of amylase enzymes, a relatively recent evolutionary adaptation to the starchy diets of agriculture. As they liquify the starch and turn it into sugar, aroma compounds volatilize. Since this happens inside the mouth, pay special attention to retronasal: the odor perception that occurs when you breathe gently out your nose after food or drink has been swallowed.

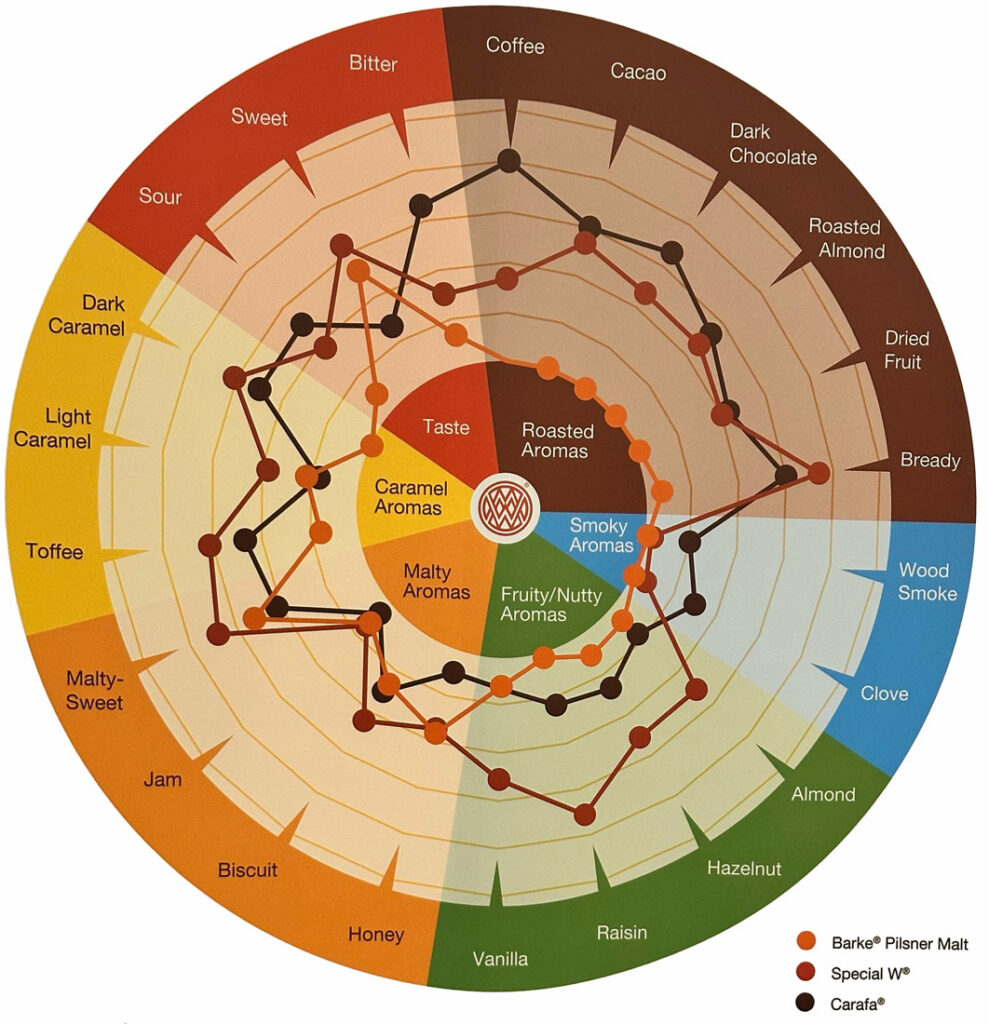

Even with this simple method, you can still learn a lot. The differences between crystal/caramel malts can be vivid even for the same type from different maltsters. Whatever method you use, be sure to record your impressions. You can use a full tasting sheet or just a blank sheet of paper and focus only on the malt aromatics. A vocabulary prompt such as a wheel is helpful, and those formatted like radar or spider charts can also be used to record intensities of attributes by putting a dot on one of the inner polygons, then connecting the dots when you’re done. Depending on the proficiency of your panelists, a tool like this wheel from Weyermann Malting offers more detail.

Malt types radar plot of complete range of brewers’ malts and covers the vocabulary fully. Thanks to the fine folks at Weyermann Malt.

Making and Tasting Malt Teas

While you can learn a lot by simply chewing on malt, trying this with the darkest varieties is pretty nasty. It’s much better to taste them in a liquid form, and if you can get test extracts from malts into an actual beer, so much the better.

A procedure generally known as the ASBC Hot Steep Malt Sensory Method was first created by Cassie Liscomb at Briess Malt in 2015, and later codified by the American Society of Brewing Chemists (see below). In its essence, malts are crushed, mixed with mash-hot water and after a 15-minute rest, are filtered before being cooled. The resulting liquid is meant to be tasted directly, without adding it to a beer.

The official procedure for base malt calls for 50 grams ground into a coarse flour in a coffee mill. For specialty (non-roasted) malts, the recommendation is to mix 25 grams each of pale/lager malt and the specialty malt. For dark roasted malts, it is suggested that 7.5 grams (0.25 oz) of dark malt be mixed with 42.5 grams (1.5 oz) of base malt, a ratio of 1:6. Burr grinders are the most consistent, but blade grinders work fine as long as you count out the same number of seconds for every batch. Just be sure to avoid cross-contamination from one malt to the next. Go from light to dark, and if you really need to clean it out, grind up some white rice or a paper towel.

The ground malt is mixed with 450 ml (15 oz) of distilled water at 65 °C (149 °F), or a little higher. This results in a ratio of 1:5 by weight, so scale this up and down as you please. After a 15-minute rest, the liquid is filtered through a paper lab or coffee filter. After cooling, the liquid can be evaluated by smelling and sipping it.

I have found it more productive to make sense of these extracts in their normal context of a beer. I use a modified procedure with a 1:2 ratio of malt to water, resulting in a much more concentrated wort. This can be added as a spike to a neutral beer such as a craft pale lager. It’s not all that revealing of very pale malts, but for darker ones—especially crystal/caramel and roasted types—it delivers a realistic sense of how each malt will work in a beer. I’ve generally used around one milliliter of this concentrated wort per 100 ml of beer, approximating a bit more than a typical usage rate for dark malts in a beer. You should experiment with the spike quantity to suit your taste and what you’re trying to achieve.

It is possible to do any of these micro-mashes with a sous-vide circulator, which works especially well when doing a bunch of samples at the same time. I’ve found that with more than a handful, it’s hard to time things so that each little mash gets the exact same soaking time, introducing some variability. By loading up all your malts and room-temperature water in little pouches, sealing them (obviously not under a vacuum), then putting them in a preheated bath, they all get the same treatment. 15 minutes after the bath comes back up to temperature, dump the water and add cold water and ice. These are stable and can sit until you filter them.

I like to cut down pre-made bags so they hold just the right amount of grain and water. I find that making them tall-ish and keeping them standing up when chilling allows them to settle a little before filtering. It’s always easiest if you run the clearest portion through the filter first, then dump in the slurry when it’s still fluid enough to do so.

Coffee filters work fine, although lab filter paper may catch more solids. With a V-type filter, a pour-over filter holder works great. Whatever funnel you use, make sure it has little ribs that allow the draining liquid to flow downwards. If you have access to some fine stainless steel or nylon mesh (a paint filter should work), make a pre-filter cone and set it right on top of the paper one. This will hold back some of the solids and make for faster draining. With larger batches, I’d recommend laboratory vacuum filtration as it’s a lot faster. For all extraction methods, after extracting and filtering, let the liquid stand for half an hour or more, then decant and leave the remaining sludge behind.

What I’ve described above are simply tiny, short mashes. Even at just 15 minutes, this still converts a fair amount of starch, so this works with paler malts. Since not all malts actually need mashing to release color, flavor and aromatics, quicker methods can be useful, particularly with crystal/caramel and roasted malts.

While it might seem like an odd idea, an espresso machine does with coffee pretty much what we’re looking for with malt: extract flavor and color, while leaving the solids behind. A single-shot espresso starts with seven to nine grams of coffee, so the samples are small. But, like my 1:2 ratio above, an espresso machiune creates a pretty strong malt extract that can easily flavor a pint or two of beer. Drip filtering can test your patience; this method bypasses it with brute force.

While these techniques are mainly meant for sensory evaluation, they can also be used in recipe development and tabletop prototyping. It’s even possible to prototype grain bills to some extent, either by blending different amounts of these quickie mashes, or by test-mashing a proposed grain bill. If you want to scale this up to a full recipe, it’s important to be accurate in your measurements and notes. With a particular ratio of malt to water and an amount of the resulting test extract added to a beer, it should be possible to simply do the math to figure out what the equivalent amount of the malt(s) should be used in the full-scale recipe.

It’s also easy to experiment with techniques like cold-soaking, which can produce, as with cold-brew coffee, smoother and less pungent results. Scaling up to a brew, these cold infusions can be filtered and added at flame-out. Since brewing can be cumbersome and slow, it’s great to taste quickly through a lot of options, making better beer and, as a bonus, a more capable model in your head.

Link to the ASBC Malt Tea Procedure:

https://www.brewingwithbriess.com/blog/the-hot-steep-method-step-by-step-instructions/