© 2016, Randy Mosher

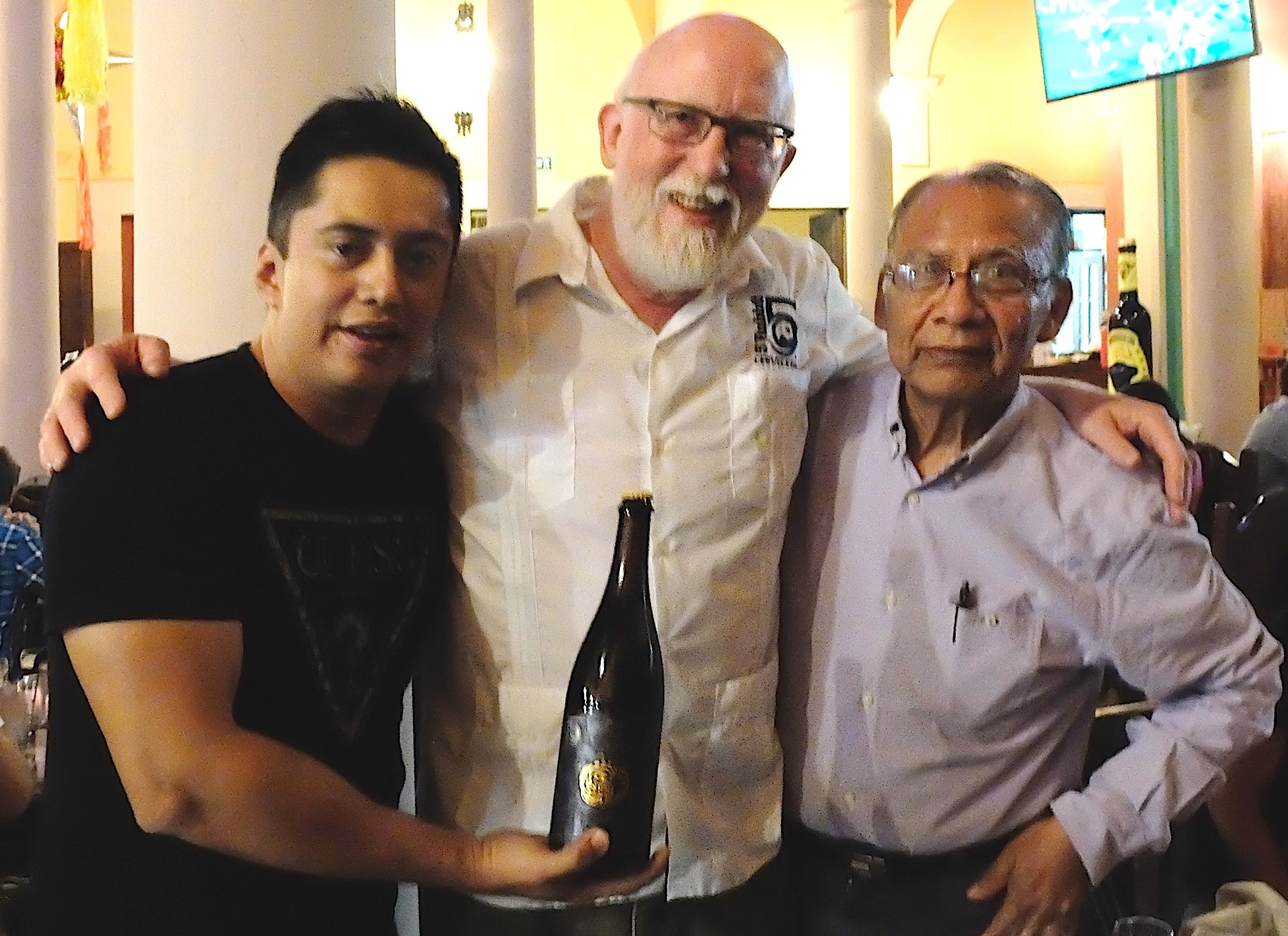

Above: I’m accompanied here by father and son Arturo Elías García Gonzales and Elías García Martinez brandishing a bottle of 5 Rabbit CaCao brewed with their mamey seed.

In 2016 I was honored to be invited to judge at the Slow Food Beer competition in Celaya, Mexico. Its state—Guanajuato—had been declared to be the least gastronomically developed in Mexico, but despite that, there are some thrilling bright spots. Celaya is the heart of Mexico’s dairy goat industry, famous for its cheese as well as cajeta, a creamy caramel made from goat’s milk. More on that later.

I hop on the bus with Lucia Carillo, the competition organizer and one of those in Mexico helping develop various aspects of their nascent craft beer culture. Things are happening fast here. A recent law banned exclusivity deals between brewers and restaurants, and while there is still a very long way to go, it has cracked the door open for small brewers to get their products to consumers’ lips. A new generation of craft beer bars are popping up as well. As a result, many brewers are expanding rapidly. Another law working its way through the legislature will hopefully offer relief for small producers of beer and other artisanal products. Mexico’s punishing tax system bases tax on the cost of production, with tax multiplying through the federal, state and local levels, giving large producers a huge advantage on top of others they already enjoy. This system, similar to the one in Brazil, forces small producers to pay much more per liter on their products than the big brewers, whose costs are very low. As a result, a typical craft beer costs about twice as much as a mass-produced one, creating a barrier in a country where many people may have to think twice about the cost of a beer.

This Beer competition is taking place at a rural fairgrounds, part of a larger Slow Food event that also includes judging for dairy goats and the cheese whose milk they provide. An added bonus is a free food and drink expo, with cajeta, cheese, other food, beer, and some spirits and wine as well. Slow Food is a global organization founded in Italy to preserve food culture, traditions and heirloom varietals threatened by our increasingly industrialized food landscape. Like their biennial Salone del Gusto in Italy, there are free samples and everything is for sale. Yum. Slow Food Mexico y Centroamerica is overseen by Alfonso Rocha Robles.

We faced about a hundred beers to judge over a day-and-a-half, with a crew of nine. My table started off with herb and spice beers, which were unexpectedly fine in the morning, with some interesting beers made with nurite, a softly pepperminty herb, and also hoja santa, known as the root beer plant due to its spicy sassafras aroma. This aroma comes from safrole, which has been banned —along with sassafras— in the US since 1960. It is perfectly legal in Mexico, and from what I’ve been able to tell, the science behind the ban is pretty iffy when you actually look at mg/kg of body weight. You would have to consume impossible amounts to reproduce the problems the rats experienced back in the early space age. Used most characteristically to wrap fish for steaming in Southern Mexico, hoja santa’s intense aroma can take over a beer pretty quickly, we found.

The most fascinating aroma was from rosita de cacao (Quararibea funebris), a spice consisting of the flowers from an evergreen tree from Southern Mexico, and traditionally used to season cacao beverages. Unrelated to cacao itself, it has a really unusual aroma, with a penetrating dried flower character, along with some sake, raisin as well as some terpene-like character, perhaps somewhere between celery, coriander and parsnip, with a heavy quality a bit like truffles. It also seemed to have a touch of chocolatey perfume.

The afternoon was a little rougher. Having judged beer in Latin America several times over six years, the one universal problem is fermentation, usually showing itself with overly phenolic aromas or abundant esters of banana or nail polish. Unlike the US, dry yeast is the norm here. While there’s nothing wrong with dry yeast in theory, in practice it appears to magnify small differences in temperature and other fermentation conditions, so must be carefully selected and managed.

Like a burst of sunshine at the end of the day, things brightened. First, a deliciously layered saison with fennel, rosemary, and “native California sage” (which I’m assuming meant white sage) and honey. These are all challenging ingredients, but the beer was very well-balanced and a pretty fine saison as well. The other was a “winter ale,” brewed with piloncillo, vanilla and star anise. Piloncillo—an unrefined cane sugar—fits into beer easily, but those last two can really take over and screw up a beer. We were amazed at the subtle complexity and depth from just three special ingredients.

Before judging resumed, we had some time for the food fest and headed right for the cajeta. There was an older gentleman handing out samples in traditional small round wooden containers. This, he said, was the original cajeta, made solely from fresh goat’s milk with no added glucose. The taste was one of these experiences you have only rarely, where a single taste opens up a world of flavor and seems to go on forever. Profoundly milky, its slight sweetness balanced by salt, with rich caramelized flavors and the unmistakable funk of goat. A searing memory.

I never had the chance to fully dig into the many fine goat cheese offerings, but I sampled a few and bought a beautifully aged sheep cheese—for which I am particularly weak-kneed—and a super-smoky cow cheese along the lines of a salty, granular provolone. Artisanal cheese from Latin America is generally not on our radar, but it should be, as these were as good as anything I’ve had elsewhere. Hopefully some of these may eventually find their way north of the border. They would be welcomed with open arms.

Alfonso introduced me to a farmer specializing in Xoconostle: several varieties of wild-harvested prickly pear fruit that differ from their familiar cousins (“tuna” fruit) with a more concentrated flavor and a sharp acidity. His family produces a wide variety of products ranging from traditional salted, dried strips to purées and other bulk products. Many are available through the Rancho Gordo/Zoxoc Project, which you can find online. It will be definitely be fun to work with him in the future. He’s a savvy businessman, helping other farming families bring their beans, chiles and other products to the gourmet marketplace. He was kind enough to give me some samples, including some xoconostle (of course!) and a small red chile called “rabon,” and some of the nicest morita (chipotle) chiles I’ve ever sniffed, smoked over oak.

Friday morning’s coffee and chocolate beers were mostly disappointing—a bumpy roller coaster ride of phenol, oxidation, esters and underwhelming use of specialty ingredients. Chocolate and coffee are among the most challenging of all ingredients to incorporate into beer, so there’s definitely a learning curve. There were some gems towards the end, including two imperial stouts: one with cacao and mescal, which lent a nice fruity undertone, and another with Oaxacan Cafe Pluma (a seaside coffee known for its bold and slightly briny flavor) and Sonoran raw piloncillo sugar.

Best of show judging was done on-stage by myself, Jessica Martinez and Ricardo Briones. The beers sorted themselves out pretty well. A few with some small problems, a xoconostle gose that was very tasty except for a little phenolic astringency and a coffee beer showing some oxidation, but generally they were a pretty good bunch—as you would expect for best of show. The winners were: in third place, rosita de cacao red ale called Chica Mala from Cervecería Teufel; in second place was Tripa, a fascinating triple from Cervecería Ozocol brewed with piloncillo, adding a complex honey-ish nose. Best of show was La Bru’s Winter Beer, the dark and sophisticated blend of vanilla, piloncillo and star anise. The crowd was fortunate that brewer Matt Hikory had a five-gallon keg on hand just in case the beer did well. It tasted even better fresh from the keg.

Friday night was a Slow Food dinner party at a classic restaurant downtown. Unfortunately, there was little time to ramble, but we did get a glimpse of Celaya’s amazing spherical steampunk water tower and the curious squared-off elevated hedge that rings the main town square. After dinner, it was a tremendous honor and to meet the Oaxacan family that provided 5 Rabbit Cerveceria with the mamey seeds that added an amaretto note to our recent CaCao beer. Their company, AKIH, specializes in several rare types of indigenous vanillas pollenated by hummingbirds. These are among the most sought after of all vanillas, commanding prices as high as 4 Euros for each diminutive bean in Paris. It was a thrill to to present them with a taste of the beer, which they appeared to find satisfactory. I left them with a short wish list, and hopefully we can find a way to work together in the future. They sent me away with a sample of their precious vanilla beans, so a trial is likely in the near future.

Mexico, like other Latin countries, is an enormous reservoir of unique, flavorful and culturally important ingredients and food traditions. It’s important to preserve both the biological as well as cultural presence of these, as they are vulnerable to the forces of development and the modern world in a variety of ways. This is the important work being taken on by Slow Food and other organizations. Foods and drinks are among the most fundamental aspects of human culture, and to a great degree, define who we are. We cannot let our past slip away even as we move forward.

After the luxury bus ride (seriously!) back to Mexico City, Saturday featured a quick visit to the “laboratory” of Lucia and her boyfriend Rodrigo Romo Michellena, who is also a professional chocolatier. The place is actually a nano brewery—called Bazooka—they are using to develop recipes and work out which direction the business will go. For now, they are selling homebrew-scale batches to local bars and restaurants. They have one or more other partners, and they also rent it out to homebrewers who don’t have the space and equipment necessary to brew. So it serves as an incubator and a valuable tool for those interested in going commercial on a small scale, or just playing around with some homebrew, an equally important pursuit.

She has an English pale ale incorporating an herb called nurite, a flavor from her childhood in Cuajimalpa, in the Mexico City area. We discussed the presence of a little tannic astringency and speculated that it might be from the nurite, so some timed tea trials are in order to find the optimum soak time for aroma before extracting too much polyphenolic material, an extremely common issue with herbs and spices. He’s been developing a ginger beer with some limón, and it’s coming along nicely. They’ve both got solid technical backgrounds and tasting skills, so the future can only get brighter for Bazooka.

The day ended with a beer event at the fabulously beautiful beer bar called Fiebre de Malt (malt fever) in the graciously swanky neighborhood of Polanco. This was the first Slow Beer event ever in Mexico City. I was the featured presenter, along with Matt Hikory of La Bru. He talked about the importance of preserving local ingredients and traditions and described in detail his flagship Masa Azul Cream Ale, which employs organic blue corn from his home state of Michoacan. The beer has a soft, pleasant grainy aroma with a whiff of hops, and a dry body with some crisp bitterness. The maize, while deeply blue when harvested, loses most of its color at the low pH of beer, a fact we found out at 5 Rabbit when we attempted to use purple Peruvian maize to add color to a watermelon beer. As a result, his beer has the barest hint of pink.

I brought one big bottle each of 5 Rabbit Huitzi and CaCao. Like the biblical loaves and fishes, somehow the staff managed to serve a small sample of each to about 50 guests. I used these beers to talk about our relationship with Latin America, and how stories for us are almost as important as the beers. I also discussed our development process from prototyping to tweaking and described in detail our work with jamaica (hibiscus), chiles, and the story of our acquisition of the mamey pits. Everybody seemed to appreciate the beers. It’s great to feel like a part of their community even though I am a long way away in so many respects. It’s a beautifully open-hearted place.

Now it’s 10 pm and we’re headed for dinner at a tiny restaurant called Las Tlayudas. Lucia has been talking about her passion for tlayudas all week; they’re a Oaxacan specialty consisting of large, paper-thin tortillas with various fillings: beans, roast pork, cecina (a super-thin beef jerky), chapulines (fried and salted grasshoppers) and others. We order a deliciously creamy guacamole punctuated by the crunch of chapulines. It’s delicious. The tlayudas deliver as advertised. The tortilla is finely textured, browned in patches and a little crispy, but still with some flexibility, with a deep grainy taste from Oaxacan blue maize. Fillings are rich and satisfying; salsas are fabulously fruity, but pretty hot for a gringo like me.

I had a nonalcoholic beverage called tejate, a mix of water, cacao, maize, cinnamon and the rosita de cacao I mentioned earlier. It comes served in a jícara, a bowl made from the gourd-like fruit of a tropical tree. It is served with a spoon to stir occasionally, keeping the solids in suspension. It’s very liquid rather than creamy, with just a slight sweetness. The cacao and the rosita de cacao are the main flavors, with the corn masa providing a bit of a sandy texture. It’s a very traditional beverage going back to prehispanic times—a deep drink of the past that leaves me wanting much, much more.

Thanks

I want to thank Alfonso Rocha Robles and Slow Food Mexico y Centroamerica for generously bringing me down for this event. And also a special thanks to Lucia Carillo for escorting me around and prevented me from getting into too much trouble. Thanks also to the judges, volunteers, brewers and others that made me feel so welcome in their home. As I always say, the beer world is very small. We will all cross paths again very soon, I hope.

Update: Lucia and Rodrigo are still partners, working together to grow their new beer brand: Itañeñe

Below, top to bottom, left to right: 1) Mexico is Cool! 2&3) The main bar and cold room at Fiebre de Malta in Mexico City. 4) Cajeta, smoked cheese and much more at the Slow Food Expo. 5) A display of heirloom maize varieties at the Slow Food Expo in Celaya, Guanajuato. 6) BJCP judges Jessica Martinez and Jessica Carrera Herrera taste fruit ales. 7) Rodrigo and Lucía at their “nano-nano” brewery in Mexico City. 8) Tlayudas at Las Tlayudas in Mexico City; dark bits in the guacamole are chapulines (salted fried grasshoppers). 9) 5 Rabbit beers: cacao beer, simply identified by the Mayan glyph “ka-ka-wa” (label background features chupacabras and dismembered chickens), and Huitzi, a strong Belgian blonde with Thai palm sugar, hibiscus and baby ginger, named after the Aztec god of war—sometimes represented as a hummingbird—Huitxilopochtli.